Setsubun – literally seasonal division – is a religious festival that usually takes place on February 3rd in Japan, and it marks the last day of winter. It dates back more than 1000 years, and was introduced in Japan as a part of the New Year’s festivities in the lunar calendar. Because of this, the main part of the setsubun festivities is the driving out of the demons of last year, bad habits and bad luck may stay behind as well.

The way to do this is very interesting: One throws fukumame – lucky beans – at the demons while shouting “Oni wa soto” (demons outside) and one eats the beans with a hearty shout of “fuku wa uchi” (luck inside). This mamemaki ceremony is done in many Japanese homes at 5 pm, and it is great fun for kids. Somebody of the family will wear a demon mask, and the kids are allowed to throw beans at the demon, all the while shouting on top of their lungs. Even some of my adult friends do the shouting! As for the “fuku wa uchi” part, once the oni are out the door, people are supposed to eat the fukumame, one for each year of their lives plus an extra one for the coming year.

The way to do this is very interesting: One throws fukumame – lucky beans – at the demons while shouting “Oni wa soto” (demons outside) and one eats the beans with a hearty shout of “fuku wa uchi” (luck inside). This mamemaki ceremony is done in many Japanese homes at 5 pm, and it is great fun for kids. Somebody of the family will wear a demon mask, and the kids are allowed to throw beans at the demon, all the while shouting on top of their lungs. Even some of my adult friends do the shouting! As for the “fuku wa uchi” part, once the oni are out the door, people are supposed to eat the fukumame, one for each year of their lives plus an extra one for the coming year.

Many people also visit a shrine or temple for setsubun to take part in the mamemaki. Often, not only beans are scattered there, but among them little gifts or coupons for larger prizes. In the larger shrines, celebrities like actors, sumo wrestlers, or Geisha who were born under the same zodiac sign as the coming one (they are called toshi-otoko or toshi-onna) perform the mamemaki, and the visitors can get quite rough in order to catch the prizes.

The banishing of the demons itself is a religious ceremony. In Kyoto, Yoshida shrine has the largest setsubun festival, and in a shinto ritual, complete with music and dance, and archers who are actually shooting arrows at the oni, three demons are vanquished that have come to the shrine from the mountains and threatened the people on the way. I have not quite found out the precise meaning of the figure with the four eyes, but he does not seem to be a demon himself, rather the one who does or helps with the banishing.

The banishing of the demons itself is a religious ceremony. In Kyoto, Yoshida shrine has the largest setsubun festival, and in a shinto ritual, complete with music and dance, and archers who are actually shooting arrows at the oni, three demons are vanquished that have come to the shrine from the mountains and threatened the people on the way. I have not quite found out the precise meaning of the figure with the four eyes, but he does not seem to be a demon himself, rather the one who does or helps with the banishing.

However, the colours of the demons do have meaning, and there are five different oni easily distinguishable by the colour of their skin (since they only wear loincloths):

However, the colours of the demons do have meaning, and there are five different oni easily distinguishable by the colour of their skin (since they only wear loincloths):

red: avarice

blue: anger and irritation

yellow: selfishness

green: ill-health

black: complaining and hesitance

Once the ceremony is over and the demons of last year are defeated, the oni return to the mountains, no further threat for the people residing below.

Some shrines also have a bonfire later in the evening, where people can bring last year’s omamori amulets and similar things to have them ritually burned.

A very interesting – and unfortunately, almost forgotten custom – is dressing up in disguises, wearing different hairstyles or even crossdressing altogether. The latter custom is still maintained by the Geiko in Kyoto and their clients, who dress up as the other sex when meeting on setsubun.

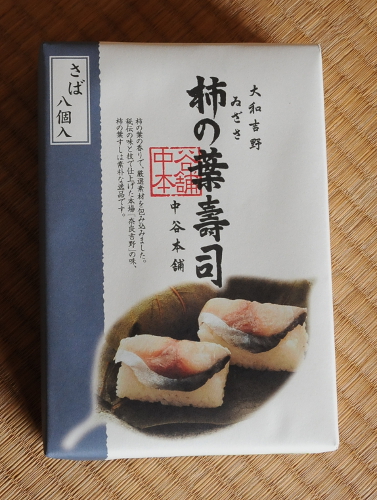

Of course, no Japanese festival can do without special food. Except for the fukumame, people are supposed to eat sardines with grated daikon radish, and then put the fish heads on the doorpost together with holly leaves to drive away the demons who apparently don’t like the smell of fish. As accompaniment, ginger sake is drunk.

A relatively new culinary custom has its origin in Osaka: eating ehomaki, literally lucky direction roll. Nothing more than a usual fat sushi roll, one must eat the whole, uncut (!) roll in one sitting without speaking and while facing the lucky direction of the year, which depends on the current Chinese zodiac. This year’s eho is north-north-west, by the way.

A relatively new culinary custom has its origin in Osaka: eating ehomaki, literally lucky direction roll. Nothing more than a usual fat sushi roll, one must eat the whole, uncut (!) roll in one sitting without speaking and while facing the lucky direction of the year, which depends on the current Chinese zodiac. This year’s eho is north-north-west, by the way.