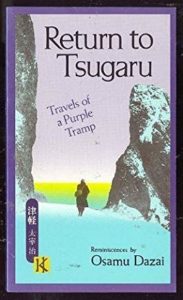

Jiro Nitta

In 1902, war with Russia seemed imminent in Japan. In order to prepare and gain necessary data for a winter campaign in Siberia, the Japanese military in Aomori Prefecture conducted a training mission in late January: 210 Japanese soldiers were sent across snowbound Mt. Hakkoda. En route of what was planned to be a short excursion of no more than three days, insufficient preparations and an unclear chain of command met with the worst blizzard of the century, leading to the death of 199 of the men involved.

This “documentary novel” presents a fictionalized account of this tragic incident, which, once word gout out, caused a public outcry that was nonetheless forgotten once the war with Russia started two years later. Equally forgotten was the fact that a much smaller group of soldiers crossed the mountain from the other direction at the same time; however, their planning proved sufficient, so they did not incur any losses.

This book describes both campaigns in great detail, from the planning stages to the soldier’s provisions and outfits, and the aftermath. It also uses survivor’s accounts and military documents (as far as they were available in 1971) that add veracity to the fiction. Yet, the author takes some liberties also. The biggest is certainly the rivalry between the two groups, ostensibly set up by their commanders, but entirely fictional. However, even for the surviving group, the march was harrowing, and Nitta does a great job documenting this.

Jiro Nitta is the pen name of Hiroto Fujiwara, a popular writer of historical novels. Born 1912 in Nagano Prefecture, he became a meteorologist and worked at the Japan Meteorological Agency. After retiring from the JMA, he began writing, many of his books are connected to mountains or mountaineering themes. He received the 1955 Naoki Prize and died in 1980 in Tokyo.

For a touching account of one of Japan’s greatest military losses in peace time, the book is available at amazon.