I have written a little about Japanese New Year’s Traditions last year, and I bet I will be writing on this subject more often 😉 Again, I will focus on the things I have done myself this year.

Just like last year, but this time alone, I went to the other side of Yoshida hill to the joyo-no-kane, the ringing of the bells. I went to Kurodani temple and listened to the bell being rung over and over again. Instead of waiting in line to do my own ringing, I went inside the temple, where monks where holding a ceremony. It was a Buddhist ceremony, and while the bell was ringing outside, four or five monks were banging sticks, sounded a sounding bowl, and recited the name of the Buddha over and over again: Namu Amida Butsu, Namu Amida Butsu…

There are many Buddhist sects, but there is that one tradition for everybody, which teaches that anyone can be saved and go to heaven after death who is sincerely calling upon the name of the Buddha. Namu Amida Butsu literally means Homage to Infinite Light, but it can have other ideas behind it depending on the sect. In Japan, Butsu is the Japanese version of Buddha and Amida means as much as merciful.

While they were having the ceremony, people wandered in and out, praying together with the monks or alone, while all through the bell kept ringing outside. As I had no idea how long the ceremony would take, and it was cold in the temple (although it was a bit warmer than last year), I left after a while and went down to Okazaki shrine for my Hatsumode.

Hatsumode is the very first shrine visit in the year, and people pray there and buy Omikuji fortune-telling slips or Omamori charms. There are many different charms for all sort of things available, and this year I bought one myself: a general happiness-increasing charm in bright yellow.

Hatsumode is the very first shrine visit in the year, and people pray there and buy Omikuji fortune-telling slips or Omamori charms. There are many different charms for all sort of things available, and this year I bought one myself: a general happiness-increasing charm in bright yellow.

It already made me very happy: Yesterday evening and all through the night fell Hatsuyuki, the first snow of the year. In fact, Japanese people are very aware of everything that happens or they do for the first time in a new year. I guess many people stay up to see the Hatsuhinode – the first sunrise of the new year. New snow of course invites Hatsusuberi, the first skiing (not for this odd Austrian though), and there is Hatsubasho – the first sumo event – some time in mid January. Hatsuyume – the first dream – is of course very important, and if you can’t sleep, there is always the Hatsuuri or first sale of the year, often with lucky bags that contain surprise items at very decreased prices and may require people to line up in front of the shops. By the way, I have invented my own New Year’s tradition, which I intend to keep up for a long time to come: Hatsuchoco, the first chocolate of the year…

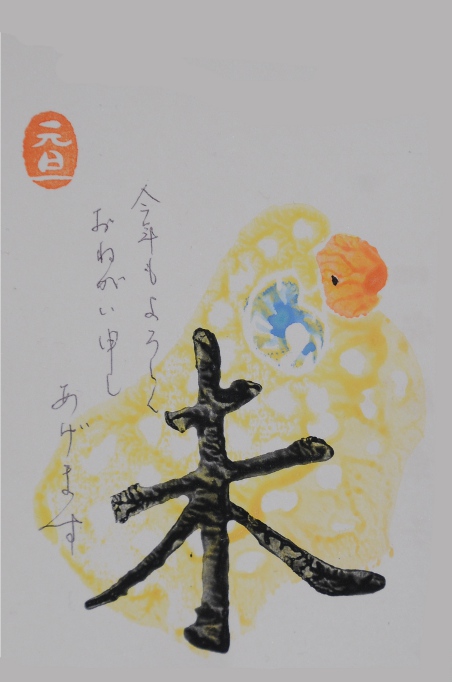

It does not really count towards Hatsudayori – the first exchange of letters – because those cards are prepared well in advance in December; but quite early in the morning on January 1st you will receive New Year’s cards, nengajo. Many people of an artistic bent spend lots of time in making their own, just as my friend has: