Matsunoo Taisha – lovingly called Matsuo-san by the locals – marks the western end of Shijo dori with its large torii. Matsunoo Taisha was established in 701 by Hata-no-Imikitori, the head of the local ruling clan. The story goes that he saw a turtle (a sign of luck and longevity) in a waterfall and decided to build a shrine here. However, the locals had worshipped a certain boulder on the mountain for a long time before that already. In any case, Matsunoo Taisha is one of the oldest shrines in Kyoto, and the Hata clan was instrumental in moving the capital to Kyoto eventually.

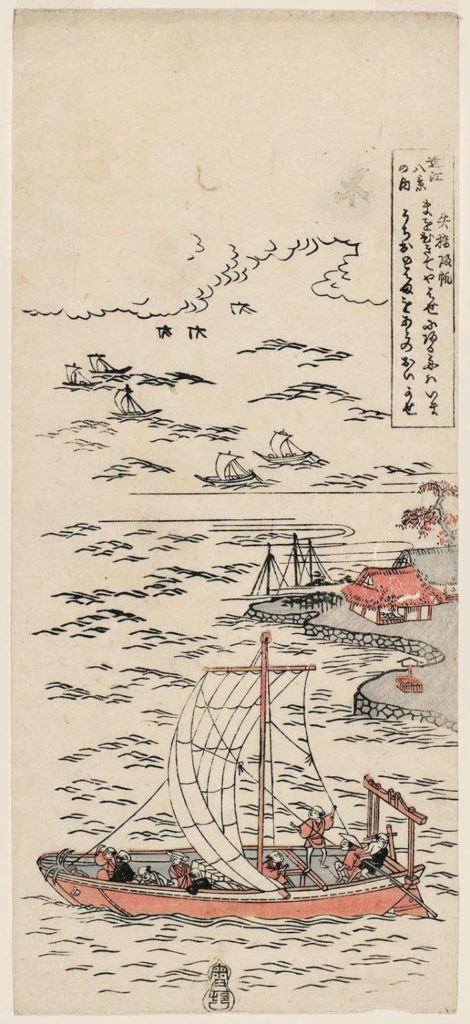

The two main gods enshrined at Matsunoo Taisha are O-yamagui-no-kami, the god of brewing sake and of Matsuo-san, the mountain behind the shrine; and Ichiki-shima-hime-no-mikoto, a female deity protecting travellers.

The two main gods enshrined at Matsunoo Taisha are O-yamagui-no-kami, the god of brewing sake and of Matsuo-san, the mountain behind the shrine; and Ichiki-shima-hime-no-mikoto, a female deity protecting travellers.

The main entrance of Matsunoo Taisha is at the large, 14m high torii at the western end of Shijo street. A smaller road leads to the main shrine, where there is another torii. From there, the path leads up some steps to the two-storey Romon gate, which is – like the one at Yasaka shrine across the city – guarded by two zuishin warrior statues to the left and right.

Passing through the gate, at first, there is a small stone bridge to cross, and a few more steps lead directly up to the dance stage. At the left of it is a large display of sake barrels. While these are common donations to shrines, Matsunoo Taisha, as home of the god of sake brewing, has received a large number of barrels originating from sake brewers from all over Japan.

Passing through the gate, at first, there is a small stone bridge to cross, and a few more steps lead directly up to the dance stage. At the left of it is a large display of sake barrels. While these are common donations to shrines, Matsunoo Taisha, as home of the god of sake brewing, has received a large number of barrels originating from sake brewers from all over Japan.

Behind the dance stage lies the long haiden outer hall where people worship and behind that, the impressive honden main hall. This is the oldest building of the shrine, dating back to 1397 and is designated Important Cultural Asset. Its unusual roof – in the so-called Matsuo-zukuri style – forms porticos on the back as well as in the front of the building.

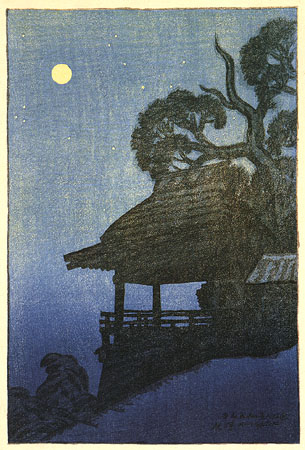

After praying at the haiden, go to the right and through the low entrance to the back of the shrine where a path leads uphill. To the right, there is the famous Kame-no-i well, where a large black turtle spews holy water. It is said, that this water will bring health and longevity to those who drink it. Even more importantly: If sake is brewed with even a small fraction of this water, it will not go bad. Therefore, many sake brewers visit the shrine regularly to get some of the water, and to pray for business success. Further up the path lies the shrine’s sacred waterfall Reiki-no-taki, which marks the spot where Hata no Imikitori allegedly watched the turtle swim all these years ago.

After praying at the haiden, go to the right and through the low entrance to the back of the shrine where a path leads uphill. To the right, there is the famous Kame-no-i well, where a large black turtle spews holy water. It is said, that this water will bring health and longevity to those who drink it. Even more importantly: If sake is brewed with even a small fraction of this water, it will not go bad. Therefore, many sake brewers visit the shrine regularly to get some of the water, and to pray for business success. Further up the path lies the shrine’s sacred waterfall Reiki-no-taki, which marks the spot where Hata no Imikitori allegedly watched the turtle swim all these years ago.

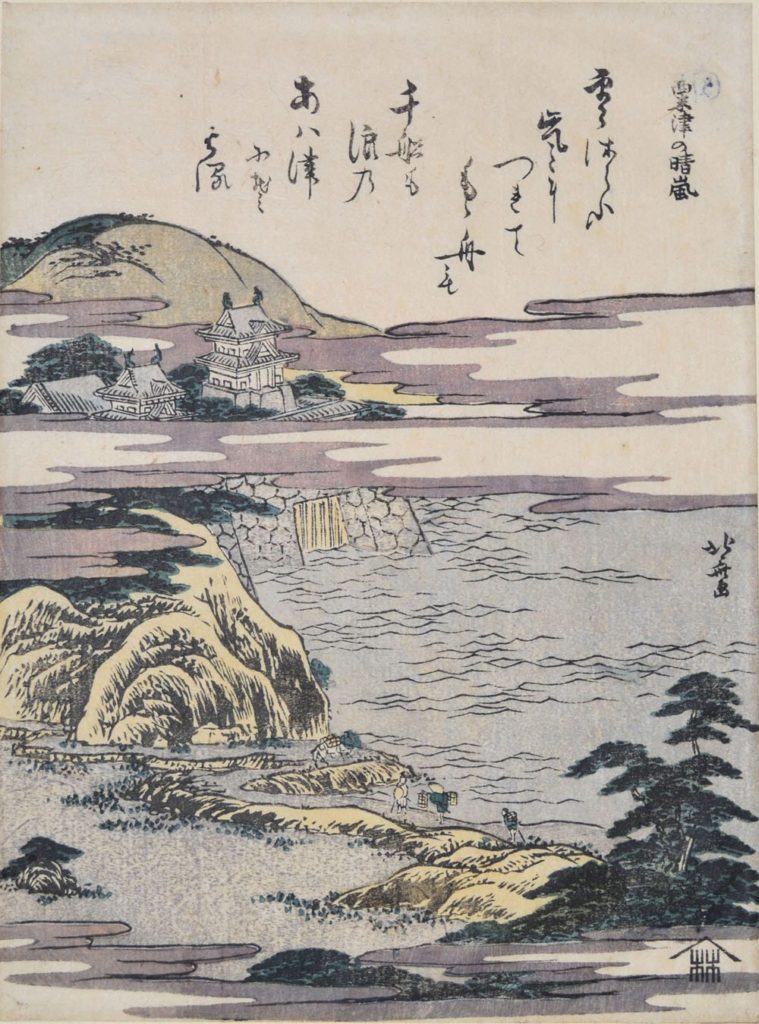

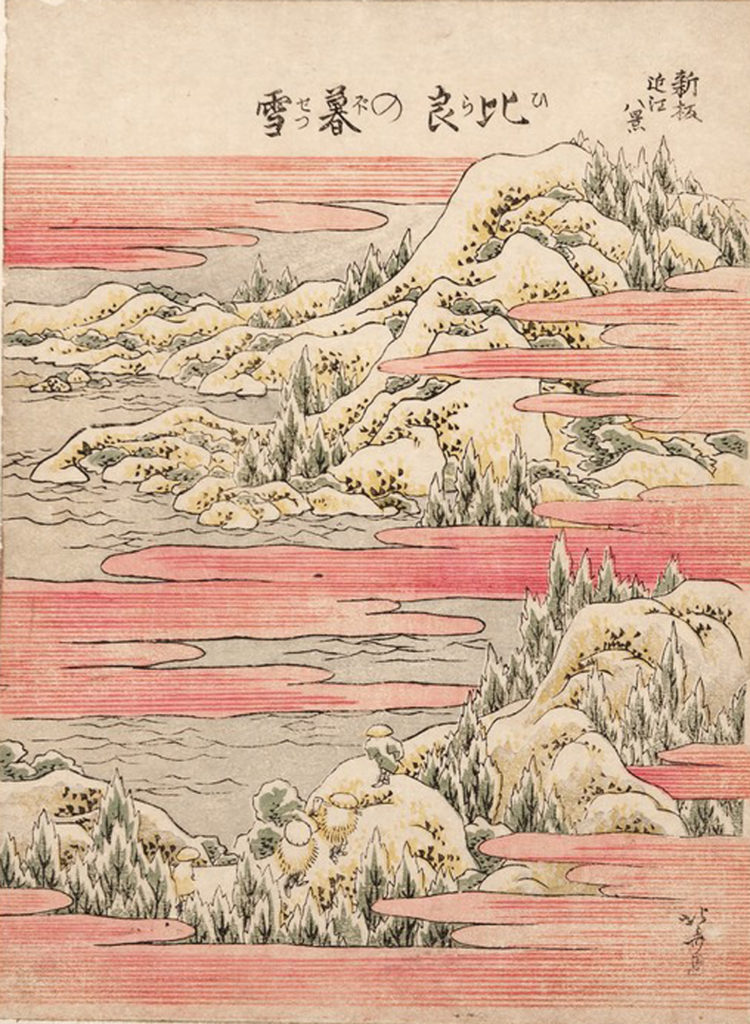

Nearby the Kame-no-i well lies the entrance to two of the three gardens that make up the Shofu-en garden of Matsunoo Taisha. They were designed by the late Mirei Shigemori just before his death in 1975 and are considered the best modern gardens in Japan. Each of the three parts of the garden is representative of a Japanese era, and the opposing ideas of stillness and movement, represented by large blue-green rocks and water, respectively, are the central design elements.

Nearby the Kame-no-i well lies the entrance to two of the three gardens that make up the Shofu-en garden of Matsunoo Taisha. They were designed by the late Mirei Shigemori just before his death in 1975 and are considered the best modern gardens in Japan. Each of the three parts of the garden is representative of a Japanese era, and the opposing ideas of stillness and movement, represented by large blue-green rocks and water, respectively, are the central design elements.

The first garden behind the entrance is the Kyokusui garden, with a stream of water bending seven times around heavy rocks. The stream is framed by smaller stones, giving it the appearance of a dragon, a water creature in Japanese mythology. The Kyokusui represents the gardens popular at the Heian era, the time of the foundation of Kyoto.

Beyond the Kyokusui lies the Iwakura or Joko garden, where a number of large rocks scattered on a steep slope represent the ancient times, where the gods roamed the mountain tops of Japan. The two largest rocks on top of the slope are meant to represent the main gods of the shrine. Beyond this garden, there is a path further up the mountain where the original place of worship, the iwakura stone, can be visited.

Beyond the Kyokusui lies the Iwakura or Joko garden, where a number of large rocks scattered on a steep slope represent the ancient times, where the gods roamed the mountain tops of Japan. The two largest rocks on top of the slope are meant to represent the main gods of the shrine. Beyond this garden, there is a path further up the mountain where the original place of worship, the iwakura stone, can be visited.

The third garden, the Horai (the entrance is next to the little restaurant outside the Romon gate), is constructed in the Kaiyu style, where a large pond shaped like a crane is the central focal point. The basic idea here is the Chinese concept of paradise, where people do not get old or die. The rocks represent islands in the sea, and the only movements are contributed by the fountain of youth in the back of the garden and the many carp in the pond.

Besides the extensive shrine gardens, which are a rare feature in Shinto shrines, Matsunoo Taisha also has two museums. The treasure hall is the main museum; it is situated between the first two gardens and shows 21 wooden statues in total. The three largest ones date back to the Heian period and are among the oldest and best preserved wood carvings of Japan. Although they are carved in the style of Buddhist statues, two of them are said to show the main Shinto deities of the shrine. These statues with their beautiful serene expressions are among Japan’s national treasures and alone justify a visit to the shrine.

Besides the extensive shrine gardens, which are a rare feature in Shinto shrines, Matsunoo Taisha also has two museums. The treasure hall is the main museum; it is situated between the first two gardens and shows 21 wooden statues in total. The three largest ones date back to the Heian period and are among the oldest and best preserved wood carvings of Japan. Although they are carved in the style of Buddhist statues, two of them are said to show the main Shinto deities of the shrine. These statues with their beautiful serene expressions are among Japan’s national treasures and alone justify a visit to the shrine.

The other museum lies near the entrance, on the way to the parking lot. The little Sake-no-shiryokan shows old tools that were once used to produce sake. They were donated by sake makers worshipping the god of sake brewing here.

Matsunoo Taisha lies a bit off the beaten tracks of Kyoto’s Arashiyama area, but especially during April and May, when the shrine’s 3000 yellow Kerria bushes are in bloom, it has a distinct charm that should not be missed. The shrine sells a number of unique lucky charms, for example one representing a bright yellow Kerria flower. However, for extra luck, you should try to win your omamori at the game shooting arrows at empty sake barrels.

Matsunoo Taisha lies a bit off the beaten tracks of Kyoto’s Arashiyama area, but especially during April and May, when the shrine’s 3000 yellow Kerria bushes are in bloom, it has a distinct charm that should not be missed. The shrine sells a number of unique lucky charms, for example one representing a bright yellow Kerria flower. However, for extra luck, you should try to win your omamori at the game shooting arrows at empty sake barrels.

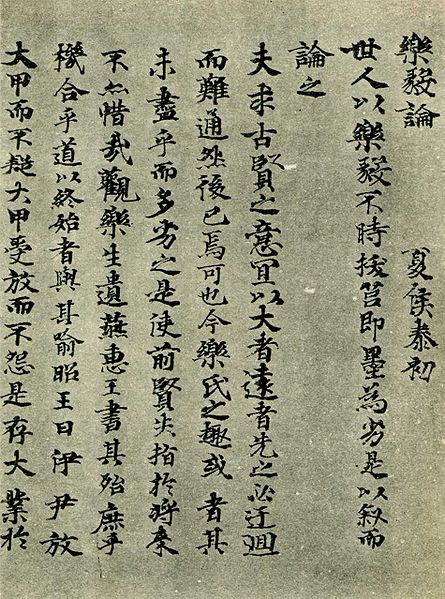

Nintendo is a very old company, founded in 1889 in Kyoto. The name’s Kanji can be translated as “leave luck to heaven”. At first, the company produced handmade hanafuda playing cards, which were quite popular because of their simple design. However, those cards were almost always used for gambling, something the government tried to restrict, especially from the Meiji period. One way out of this was to produce different sets of cards every time one particular game became illegal. However, in 1959, Nintendo had a brilliant idea: They made a deal with the Disney company, allowing them to use Disney designs on their playing cards. In this way, the cards could be marketed to families with children – and in one year, more than 600.000 packs were sold.

Nintendo is a very old company, founded in 1889 in Kyoto. The name’s Kanji can be translated as “leave luck to heaven”. At first, the company produced handmade hanafuda playing cards, which were quite popular because of their simple design. However, those cards were almost always used for gambling, something the government tried to restrict, especially from the Meiji period. One way out of this was to produce different sets of cards every time one particular game became illegal. However, in 1959, Nintendo had a brilliant idea: They made a deal with the Disney company, allowing them to use Disney designs on their playing cards. In this way, the cards could be marketed to families with children – and in one year, more than 600.000 packs were sold.