Ohara is a sprawling rural community situated in a wide plain (hence the name) northeast of Kyoto. It still belongs to Kyoto, even though it lies more than 30 minutes by bus outside of what I would consider the city limits. Ohara is famous for its oharame – local women who used to peddle firewood, flowers or produce in Kyoto – Sanzen-in Temple with its beautiful moss gardens, and the former nunnery Jakko-in.

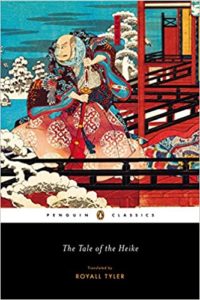

Jakko-in is a tiny temple that lies in the opposite direction of Sanzen-in at the end of a little valley. The walk there is very pleasant, it leads first along a little stream, then though the community. Judging from the number of souvenir shops and cafes on the way, it must be less popular than Sanzen-in. And had it not been mentioned in the Heike Monogatari, I guess it would have been forgotten long ago.

But let’s start at the beginning, in 594, when the temple was established by Shotoku Taishi to pray for the soul of his father, Emperor Yomei. At that time, Buddhism had only recently been introduced to Japan. Therefore, one of the first nuns of the country (who also happened to be the wet nurse of Shotoku Taishi) moved to the temple. Subsequently, Jakko-in became a retreat for nyoin, female members of the Imperial family and daughters of other high-ranking families. It seems, however, that taking vows was not a requirement to live there.

According to the temple, the third nun only moved there in 1185, and it’s because of her that Jakko-in is famous to this day. Her name was Kenreimon-in Tokuko, daughter of Taira-no-Kiyomori and mother of Emperor Antoku. Sounds familiar? The Taira (or Heike) fought against the Minamoto (or Genji) clan in the Genpei War (1180–1185), which was immortalized in the Heike Monogatari mentioned above. Sadly, the entire Taira clan was wiped out , and even Emperor Antoku, a mere boy of 6 was killed. Kenreimon-in spent the rest of her days in Jakko-in praying for the souls of her son and relatives.

From the temple’s entrance, stone steps lead straight up to the main hall. It is home to a statue of Rokumantai-Jizoson, the protector of children. There are also wooden statues of Kenreimon-in and her servant Awa-no-Naishi, only the second nun ever to live at the temple. Her garments are said to have been the model for the oharame’s clothes.

Sadly, none of this is original, not the building, and not the statues either. The temple was burned down in an arson attack in May 2000, and all you can see are reproductions. The main statue especially looks very modern; it is dressed in a colorful garment that I would call garish to the point of kitsch. However, on asking, I was told that that this is the original look of the statue when it was – supposedly – created by Shotoku Taishi himself, according to old documents.

To find out more about the temple, the nuns, and the arson attack, you can visit the treasure house which holds a lot of artifacts. The most interesting of these are more than 3000 wooden statues of Jizo, roughly 10 cm tall, that were all found inside the main statue after the arson. The original, badly burned statue, an Important Cultural Asset, is not usually on display.

Since the temple is so small, the gardens are not very extensive. The ones surrounding the main hall are the most beautiful, and there is a stump of a 1000-year-old pine that sadly did not survive the fire. It is said that this part has been maintained since the time of the Genpei War, and right now, you can hear tree frogs croaking in the little pond beneath the former pine. Another pond with koi carp and a little waterfall lies to the north of the main hall, and on a lower level, there is a tea house with yet another pond in front of it.

Kenreimon-in is still present at the temple. Just south of the main hall, a marker indicates her former residence, and once you leave the temple and take the steps uphill just outside of it, you can visit her tomb.

All in all, I found Jakko-in a nice experience. I like to visit places that are not overrun by tourists, and being just a bit off-season does help as well in this respect. The staff are very friendly and happy to answer questions.