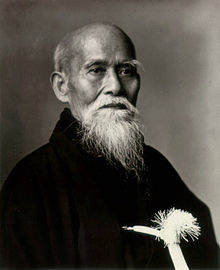

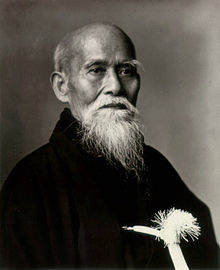

Aikido – literally harmonic spirit path – is a modern Japanese budo or martial art. It was developed by Morihei Ueshiba – now reverently called Osensei – in the early 20th century, starting from the time when he was around 20 years old all through his life until his death in 1969 with 85 years.

Osensei, born in 1883 was a sickly, weak child, and to strengthen his physique, he was sent to take martial arts lessons. Although his father wanted him to eventually take over the family business, Ueshiba – by then a strong young man – took a number of similarly minded people to Hokkaido, where he established a farming enterprise – today we would probably call it a commune – with mixed success. Around this time, he met two people who proved essential for his future path: He met Takeda Sokaku, a master swordsman and martial artist, and he studied what was then called aiki-jujutsu under Takeda for more than 10 years. After that, he joined the Omoto-kyo sect under its spiritual leader Onisaburo Deguchi and opened his first own dojo in Ayabe. Following his spiritual enlightenment as he called it, he went to Tokyo to open a dojo and there, he fused Deguchi’s spiritual ideas and Takeda’s martial arts into the round and soft movements today known as Aikido.

Osensei, born in 1883 was a sickly, weak child, and to strengthen his physique, he was sent to take martial arts lessons. Although his father wanted him to eventually take over the family business, Ueshiba – by then a strong young man – took a number of similarly minded people to Hokkaido, where he established a farming enterprise – today we would probably call it a commune – with mixed success. Around this time, he met two people who proved essential for his future path: He met Takeda Sokaku, a master swordsman and martial artist, and he studied what was then called aiki-jujutsu under Takeda for more than 10 years. After that, he joined the Omoto-kyo sect under its spiritual leader Onisaburo Deguchi and opened his first own dojo in Ayabe. Following his spiritual enlightenment as he called it, he went to Tokyo to open a dojo and there, he fused Deguchi’s spiritual ideas and Takeda’s martial arts into the round and soft movements today known as Aikido.

Aikido is generally considered an inner martial art, that is, the focus does not lie on increasing physical strength but on developing inner energy called ki. Nevertheless, Aikido is highly effective if done correctly. Aikido is strictly defensive and uses no weapons. The basic idea is to take an attacker’s force and turn it – using round movements – against him; hence, the force is never blocked but always redirected. The techniques fall into a type of pin, rendering the attacker unable to move, and into a type of throw, where the attacker is moved further. The total number of kata techniques is quite limited (for example, there are only six types of pins), but together with a number of different types of attacks and the distinction of receiving an attack standing or sitting, those basics already take a long time to learn: Depending on the dojo, you can expect to train between three and six years for your shodan, the first grade black belt.

Aikido is generally considered an inner martial art, that is, the focus does not lie on increasing physical strength but on developing inner energy called ki. Nevertheless, Aikido is highly effective if done correctly. Aikido is strictly defensive and uses no weapons. The basic idea is to take an attacker’s force and turn it – using round movements – against him; hence, the force is never blocked but always redirected. The techniques fall into a type of pin, rendering the attacker unable to move, and into a type of throw, where the attacker is moved further. The total number of kata techniques is quite limited (for example, there are only six types of pins), but together with a number of different types of attacks and the distinction of receiving an attack standing or sitting, those basics already take a long time to learn: Depending on the dojo, you can expect to train between three and six years for your shodan, the first grade black belt.

From there, everything else takes a lifetime. Clearly it makes a difference whether your attacker is a 150 kg, 2 m muscular superman who comes at you with all he’s got, or a 60 kg, scrawny nerd… The techniques remain the same, but beyond your shodan you will be expected to use less and less force and to make ever smaller movements. Really good shihan – senior teachers – hardly move at all when they smash you into the ground.

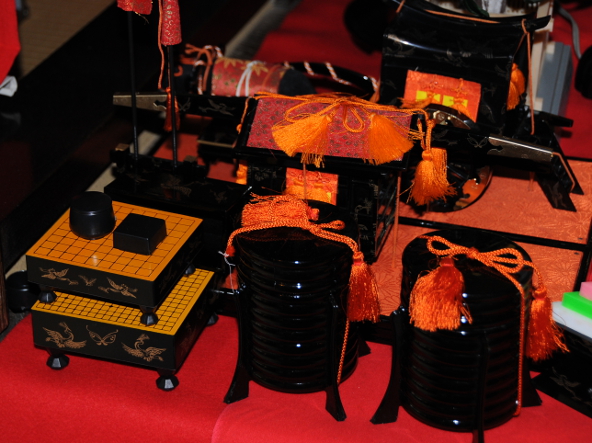

A typical Aikido lesson starts with everybody sitting in rows opposite the kamiza, the head of the dojo that usually contains a scroll or a picture of Osensei. The sensei – teacher – enters and seats himself in front of the kamiza; everybody bows first to the kamiza, and then, with a hearty onegaishimas – please – to the sensei. A technique is demonstrated, usually with one of the senior students and then the participants form pairs and try to execute the technique themselves. Usually, there is no restriction with whom you can train, beginners train with black belts, men with women… Everybody trains to their own abilities, and for the next technique, you’ll find another partner.

One of the partners is the uke – attacker – and the other is the nage – defender – who is executing the technique. As uke loses by default, there should be no competition as to who is stronger (although I know this is not always the case) and when after four attacks the roles are reversed, both partners benefit in the same way. At the end of the class, everybody bows again to sensei, then to the kamiza, and finally to the other students. Then, the black belts fold their hakama, and the dojo is swept for the next training.

partners is the uke – attacker – and the other is the nage – defender – who is executing the technique. As uke loses by default, there should be no competition as to who is stronger (although I know this is not always the case) and when after four attacks the roles are reversed, both partners benefit in the same way. At the end of the class, everybody bows again to sensei, then to the kamiza, and finally to the other students. Then, the black belts fold their hakama, and the dojo is swept for the next training.

Although Aikido incorporates many moves from sword fighting, the focus lies on empty-handed techniques, but that depends both on the style that is taught and on the particular dojo. There are a number of different styles or schools of Aikido. For example, Yoshinkan Aikido goes back to Gozo Shioda sensei, one of Osensei’s early students. It is a relatively hard style of Aikido and is taught to the Japanese police. Ki-Aikido, a further development by Koichi Tohei, is the softest style on the other end of the spectrum, focusing on Ki – a concept of energy and inner strength that is difficult to explain, even for Japanese. Iwama style Aikido is the one that emphasises weapons training the most, as it was taught to Morihiro Saito in the dojo in Iwama, where Osensei spent his later years. Shodokan or Tomiki Aikido was founded by Kenji Tomiki, another one of Osensei’s earliest students. Shodokan is the only one where regular competitions are held, and as such it is probably the most distant from Ueshiba’s principle.

The largest school of Aikido, considered the main line, at the moment headed by Osensei’s grandson Moriteru Ueshiba, is called the Aikikai, and their headquarter is still in the dojo in Tokyo that was founded by Osensei. Especially inside the Aikikai, there are many different styles, which go back to Osensei’s students of different eras. As I mentioned above, Osensei kept refining his Aikido over more than 50 years, and his techniques changed from the hard style of the young man in his prime (many students of this era went to the US to teach) over the more round style of middle age (often found in Europe) to the irresistably soft style of his old age (mainly found in Japan).

The largest school of Aikido, considered the main line, at the moment headed by Osensei’s grandson Moriteru Ueshiba, is called the Aikikai, and their headquarter is still in the dojo in Tokyo that was founded by Osensei. Especially inside the Aikikai, there are many different styles, which go back to Osensei’s students of different eras. As I mentioned above, Osensei kept refining his Aikido over more than 50 years, and his techniques changed from the hard style of the young man in his prime (many students of this era went to the US to teach) over the more round style of middle age (often found in Europe) to the irresistably soft style of his old age (mainly found in Japan).

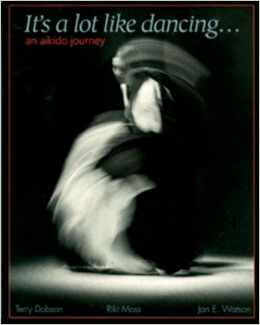

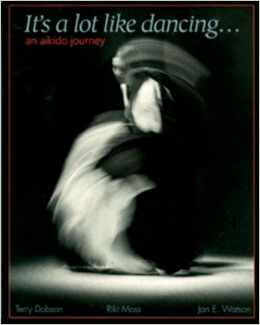

Aikido dojos of all styles can be found all over the world. If you are curious, just stop by for a trial lesson, most dojos will allow that. Finally, there are also many books about Aikido out there, from biographies of Osensei and some of his better known students down to how-to’s. My favourite book that does not talk about techniques at all, but about the greater picture behind Aikido and its place in the world is called “It’s a lot like dancing” by Terry Dobson, one of the last students of Osensei. Accompanied by stunning photographs, he shares little stories and insights he gathered from his own training over the years. Think about this one:

Aikido dojos of all styles can be found all over the world. If you are curious, just stop by for a trial lesson, most dojos will allow that. Finally, there are also many books about Aikido out there, from biographies of Osensei and some of his better known students down to how-to’s. My favourite book that does not talk about techniques at all, but about the greater picture behind Aikido and its place in the world is called “It’s a lot like dancing” by Terry Dobson, one of the last students of Osensei. Accompanied by stunning photographs, he shares little stories and insights he gathered from his own training over the years. Think about this one:

To have a war, the enemy must be kept alive.

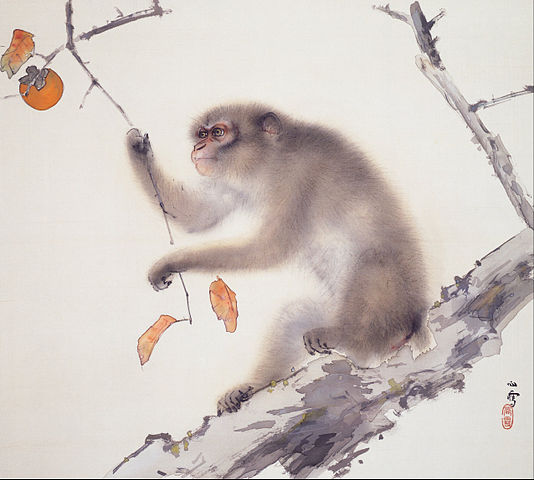

The Hakusasonso is the former residence of Kansetsu Hashimoto, a nihonga painter of the Taisho and early Showa period. He bought the site in 1913 when it was nothing more than rice paddies. Until his death in 1945, he worked on the 7400 square metres that make up the gardens now and most of it – including the buildings – are unchanged. Today, the garden is still in possession of the Hashimoto family.

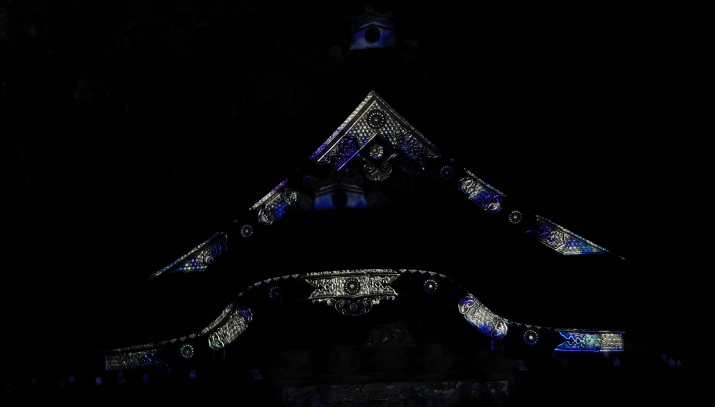

The Hakusasonso is the former residence of Kansetsu Hashimoto, a nihonga painter of the Taisho and early Showa period. He bought the site in 1913 when it was nothing more than rice paddies. Until his death in 1945, he worked on the 7400 square metres that make up the gardens now and most of it – including the buildings – are unchanged. Today, the garden is still in possession of the Hashimoto family. There are five old buildings in the garden, two small tea houses, one private Buddhist temple, and the old residence that is now used as an expensive kaiseki restaurant. The most interesting building is called zonkoro, it is essentially one very large hall that Hashimoto used as his studio. All four walls have large glass windows, and you can see almost all of the garden from the studio.

There are five old buildings in the garden, two small tea houses, one private Buddhist temple, and the old residence that is now used as an expensive kaiseki restaurant. The most interesting building is called zonkoro, it is essentially one very large hall that Hashimoto used as his studio. All four walls have large glass windows, and you can see almost all of the garden from the studio. Not only did he paint, Hashimoto also designed the buildings and the garden himself. He collected stone lanterns, pagodas, and Buddha statues (many from China) and placed them throughout the garden. Especially lovely is the little hill where Buddha statues meditate underneath large bamboos.

Not only did he paint, Hashimoto also designed the buildings and the garden himself. He collected stone lanterns, pagodas, and Buddha statues (many from China) and placed them throughout the garden. Especially lovely is the little hill where Buddha statues meditate underneath large bamboos. At one end of the garden there is the museum, a modern, two storey building where Hashimoto’s works are displayed. From the second floor of the museum, one can overlook the whole garden, and with the borrowed landscape of Mount Daimonji in the back, the scenery is made perfect. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Nihonga was a special style of painting that combined Western painting methods and ideas with Japanese materials and aesthetics. Nowadays, most Japanese painters work in truly Western style, and the distinction to Nihonga has all but disappeared.

At one end of the garden there is the museum, a modern, two storey building where Hashimoto’s works are displayed. From the second floor of the museum, one can overlook the whole garden, and with the borrowed landscape of Mount Daimonji in the back, the scenery is made perfect. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Nihonga was a special style of painting that combined Western painting methods and ideas with Japanese materials and aesthetics. Nowadays, most Japanese painters work in truly Western style, and the distinction to Nihonga has all but disappeared.