You have no idea what I have met last Sunday… But let’s start at the beginning!

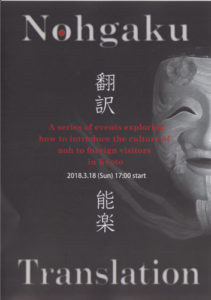

Last Sunday, I took a few hours off to take an introductory course on Noh in a very small Noh theater. Noh (or Nohgaku) is traditional Japanese theater with a history of some 600 years, and I have seen one play before. This time, however, there was an in-depth explanation of some aspects of Noh, given by three actors of both the Kanze and the Kongo theater – both major traditional Noh schools.

The course came in three parts: In the first, we got a brief historical overview, then talked about chants (Utai), masks (Omote), and movements (Kata). Two people could even try putting on one of the masks, which must have been very exciting for them. Anyway, in the second part, the movements were explored further, and the audience learnt a very short chant to which the actor then performed the moves on stage. Even though I can’t sing, this was the most fun part of them all.

In the third part, we saw a short excerpt of the Noh play “Atsumori“. But first, the most senior actor played that part with all its movements and chanted in English what was happening. Noh movements are very complex and refined, without knowing what is going on it is pretty much impossible to discern it just from watching the play. So, this part was very useful, since we could compare the English version to the stylised real version we could watch just a few moments later. I liked this part a lot, and it gave me more incentive to go back and see more Noh plays. Yes, for some odd reason, I do like Noh, even though most of it is practically incomprehensible to the outsider.

In the third part, we saw a short excerpt of the Noh play “Atsumori“. But first, the most senior actor played that part with all its movements and chanted in English what was happening. Noh movements are very complex and refined, without knowing what is going on it is pretty much impossible to discern it just from watching the play. So, this part was very useful, since we could compare the English version to the stylised real version we could watch just a few moments later. I liked this part a lot, and it gave me more incentive to go back and see more Noh plays. Yes, for some odd reason, I do like Noh, even though most of it is practically incomprehensible to the outsider.

Anyway, after the course, there was first a question and answer session, and afterwards, a few people – me included – went to have dinner in a nearby Japanese restaurant. There, the instructors of the course, the staff of the theater, and 12 people from the audience could sit together and eat, drink, and talk to the Noh actors. It turned out that the oldest one – who spoke English almost flawlessly – was the representative of a very small local Noh theatre. He was very knowledgeable, and talking to him gave me lots of things to think about.

Towards the end of the dinner, people exchanged business cards, and, you won’t believe it: That old sensei was a “Designated National Human Important Cultural Property” of Japan. These people are usually extremely knowledgeable in a traditional art of craft, and they are officially charged to maintain the art on the highest possible level and transmit their knowledge to future generations. Obviously, there are not many of them, and I am so thrilled that I could actually meet one of them – and even more: That he could speak English so well and that I was allowed to ask all sorts of questions.

Yes, I do indeed like Noh. I will be back for more!

Rakugo goes back to Buddhist monks of the 10th century, who interjected little, often humorous stories to their sermons to make them better understandable for the lay people. The stories evolved to a kind of monologue that people told among themselves, and especially the daimyo of the Edo period were the patrons of this kind of storytelling. With the rise of the rich merchant class, however, rakugo as an art form finally spread to the common people, and by the end of the 18th century, professional rakugoka had emerged, who rented rooms – yose – for their performances. Finally, theaters especially for rakugo were set up as well.

Rakugo goes back to Buddhist monks of the 10th century, who interjected little, often humorous stories to their sermons to make them better understandable for the lay people. The stories evolved to a kind of monologue that people told among themselves, and especially the daimyo of the Edo period were the patrons of this kind of storytelling. With the rise of the rich merchant class, however, rakugo as an art form finally spread to the common people, and by the end of the 18th century, professional rakugoka had emerged, who rented rooms – yose – for their performances. Finally, theaters especially for rakugo were set up as well.