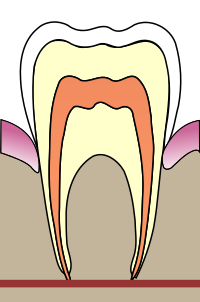

It happened again: I had to go to the dentist… Just before Christmas – of course right in a time when I was fiendishly busy – I noticed that part of an old filling had fallen out. Even though I am not an expert, I assume this is not a good thing.

It happened again: I had to go to the dentist… Just before Christmas – of course right in a time when I was fiendishly busy – I noticed that part of an old filling had fallen out. Even though I am not an expert, I assume this is not a good thing.

So I went to my dentist and made an appointment for the new year. Because I had some troubles communicating with the receptionist (a very nice woman who only speaks Japanese), the doctor was called and I explained that I probably needed a new filling. To which he responded: “Okay, I’ll have a look at it and we’ll make a treatment plan…”

Bad idea, you lost me there and then! The last time he made a treatment plan, I had to return four times for dental cleaning, one hour and 10.000 YEN each – in a private practice no less… And then already I had the feeling that he was pushing the treatment onto me without me even having a chance of declining. So the moment he said treatment plan with this smile on his face, I felt very uneasy and thought of a way to get out of this…

In fact, I did wind up sick at the time of the appointment, so I had to cancel it, and I decided not to go back but to see another dentist a friend of mine had recommended. And because I still don’t like going to the dentist (who does?) it took me until last Monday to build up the courage and finally go.

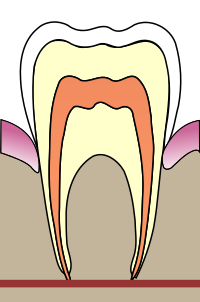

The experience was satisfactory: Last week we did the drilling (yes, I do want anaesthetics, lots of them, thank you!) and since the cavity was very large, we decided on an inlay, so we had to make dental impressions as well. Unfortunately, I have a very strong gag reflex, and the tooth was a back molar, so I almost threw up when we did the impression of the upper teeth. I’m glad it was over relatively quickly though.

Yesterday I went back to have the inlay placed, which took about 45 minutes, all said and done. Most of that time I had to wait though, and the interesting thing is that the dentist would go and treat other patients in that time. Japanese dental offices are made so that there are a number of chairs next to each other in a single room, and while one patient has to wait for example for her inlay to set, the doctor simply goes to another patient and looks at his teeth. Thankfully there are room dividers in between the chairs, but still, you can hear all the chatting and all the drilling all the time…

Interestingly I even noticed that there was a timer on the chair I sat, or rather: laid in, and the first time the doctor came over to take out the temporary filling and put in the inlay to see if it fit, he was working for exactly 1 minute and 10 seconds. I wonder if that is just a performance measure for the doctor himself, or if this is something the national health insurance mandates as part of quality control. Of course, more patients in shorter a time does not quality make, but prices are reasonable throughout. And even though I know that Japanese dentists like to do their work in many more sittings than European ones – another way to earn more money – my tooth was completely finished yesterday, and I won’t have to go back again. At least not until the next filling drops out…

Still, I have to wonder what it is in this country with dentists… The first one I went to made me feel very uncomfortable with inappropriate remarks, the second one as mentioned above was creepy and pushy. And even this one took a long and lusting look at my other 31 teeth and declared they all had cavities which needed to be fixed immediately. Nice try doc, but I am still a computer scientist: Never touch a running system! And as long as there’s no pain or missing parts, I will be fine without a complete dental overhaul at this point, thank you. Still, I think he is a good choice as a dentist: at least he can take a “no way” as an answer…

This evening there was the demon vanquishing ceremony at Yoshida Shrine, which is the largest one in the city. I just returned home, cold and tired, but at least I had lots to eat – there were many food stalls lining the entrance to the shrine. Tomorrow is the big bonfire where people can burn their old amulets and charms from last year, I brought a few of mine as well and bought a new one instead.

This evening there was the demon vanquishing ceremony at Yoshida Shrine, which is the largest one in the city. I just returned home, cold and tired, but at least I had lots to eat – there were many food stalls lining the entrance to the shrine. Tomorrow is the big bonfire where people can burn their old amulets and charms from last year, I brought a few of mine as well and bought a new one instead.