As I had to go to town on Saturday, I took the opportunity to go to an art exhibition at the Takashimaya Department Store.Yes, that’s right: at a department store. Takashimaya is one of the largest chains in Japan with stores in every large city. They are selling upscale goods and all of the international luxury brands, but not everything is prohibitively expensive. They also have a range of Japanese goods like kimono, futons, furniture, and of course, souvenirs. In the basement, there is usually a large food court, where all sorts of prepared foods can be bought, starting from onigiri to tempura, raw and fried fish, Japanese sweets and French style cakes, chocolate… On the top floor are restaurants, they are usually very good, but also rather expensive.

And on that top floor in the Takashimaya in Kyoto was the 44th Japanese Traditional Arts Exhibition. The arts ranged from woodcarving, lacquerware, to glassware and pottery. There were also little sculptures, mainly the little dolls the Japanese love so much. Of course, three walls of the grand hall displayed kimono. Although all the pieces were made in the traditional fashion, they were very modern looking.

When I entered, I was a little shocked at the amount of people. That was because somebody – probably the artist himself – gave a lengthy explanation of one of the exhibits. Once I could pass that bottleneck, the rest of the exhibition was not overly crowded.

When I entered, I was a little shocked at the amount of people. That was because somebody – probably the artist himself – gave a lengthy explanation of one of the exhibits. Once I could pass that bottleneck, the rest of the exhibition was not overly crowded.

At the exit of the grand hall was a little separate room where numerous sake cups were on display. Sake cups are interesting, they come in all sorts of sizes, shapes, and materials. I think that at least some of them were made by the artists exhibiting, and one could even buy them. A staff member came up to me and invited me to a sake tasting. At first I did not want to – it was barely noon – but I then asked whether she could explain a little about the sake and when she said she would try, I bought a ticket after all. It is not easy to find an opportunity to taste different types of sake, and this one was quite amazing.

After I had chosen three of the cups on display, I sat down on a little bar to drink. All three sake offered at the tasting were from Kyoto city itself, from Fushimi, where allegedly Kyoto’s best water can be found. Although the taste of sake is not very strong – remember that rice itself has hardly any taste at all – and I found all three of them very mild and pleasant, there was still a quite distinct difference to them. Although the taste was pretty much the same, one of them felt very heavy on my tongue, another very light – for lack of a better word, forgive me, I am not an expert. Interestingly, both of them had the same alcohol percentage, so that cannot have been the reason. I am glad I took the opportunity to do this, it is always nice to try something new.

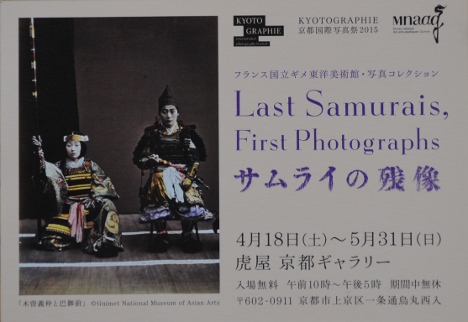

As I said, the exhibition, although small, is certainly worthwhile. It takes place in the Toraya Gallery on Ichijo dori, near the crossing with Karasuma dori, and will be open until the end of May.

As I said, the exhibition, although small, is certainly worthwhile. It takes place in the Toraya Gallery on Ichijo dori, near the crossing with Karasuma dori, and will be open until the end of May.