Hashiguchi Goyo (1880 – 1921) is a renowned Japanese artist and considered the founder of the shin-hanga style of woodblock printing.

Hashiguchi was born as the son of a samurai and painter in 1880 and was then named Kiyoshi. He started to study Japanese painting in the traditional Kano style with a private tutor when he was 10, and in 1899 he moved to Kyoto to continue his studies in the Kano style. However, the famous painter Kuroda Seiki convinced him to instead study Western painting, and so Hashiguchi enrolled in the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. Is was there that he changed his first name to Goyo – inspired by the five needle pine in his father’s garden – and he graduated in 1905 at the top of his class.

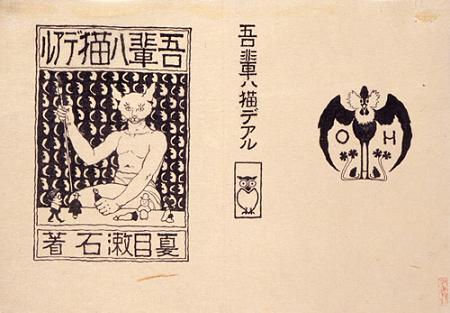

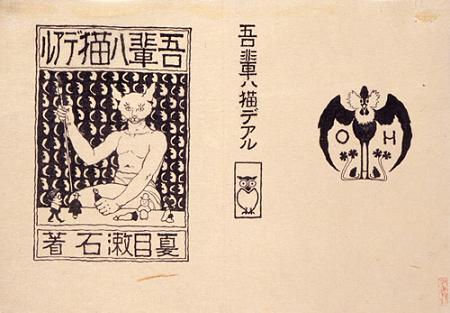

At this time his older brother introduced him to Soseki Natsume, and Goyo’s first commission was to design layout and illustrations for the novel I am a Cat. More book covers followed, all in all he designed about 70 covers in art nouveau style for various writers, among them notable ones like Junichiro Tanizaki, Nagai Kafu, or Mori Ogai.

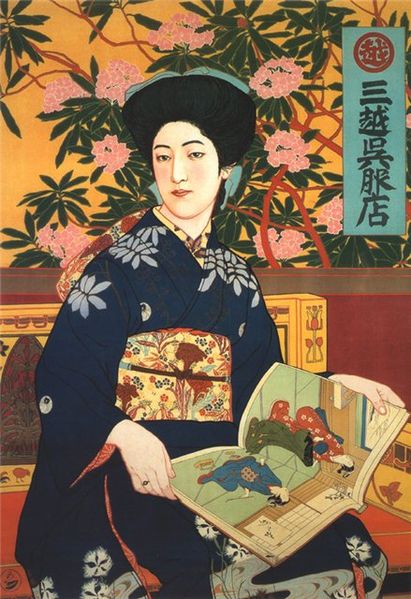

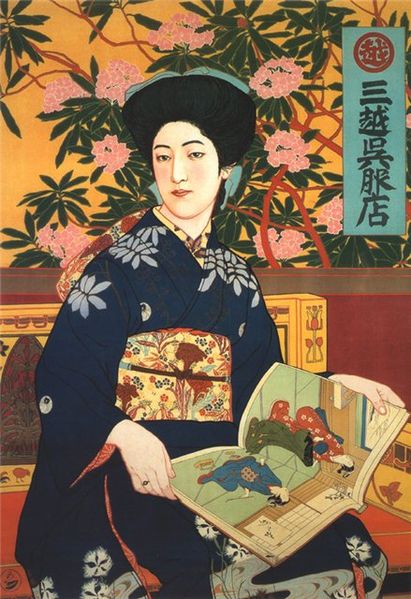

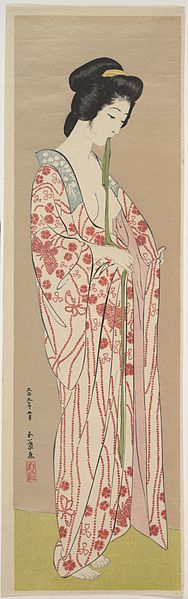

In 1907, Hashiguchi exhibited a painting in the Tokyo Bunten show, which received 2nd prize, but overall, the reception of his oil paintings was below his expectations. In 1911, however, Goyo won the first prize – 1000 yen – for an ukiyo-e poster he designed for the Mitsukoshi department store, depicting a modern Japanese woman in a colorful kimono. Hashiguchi’s interest in ukiyo-e was piqued, and he began to study art and technique in detail. He even wrote several scholarly articles about old ukiyo-e artists Utamaro, Harunobu, and Hiroshige.

In 1907, Hashiguchi exhibited a painting in the Tokyo Bunten show, which received 2nd prize, but overall, the reception of his oil paintings was below his expectations. In 1911, however, Goyo won the first prize – 1000 yen – for an ukiyo-e poster he designed for the Mitsukoshi department store, depicting a modern Japanese woman in a colorful kimono. Hashiguchi’s interest in ukiyo-e was piqued, and he began to study art and technique in detail. He even wrote several scholarly articles about old ukiyo-e artists Utamaro, Harunobu, and Hiroshige.

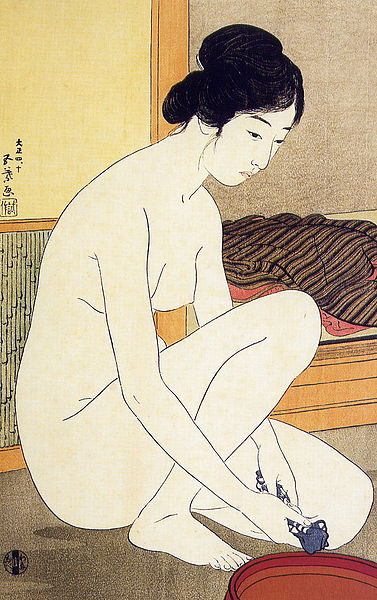

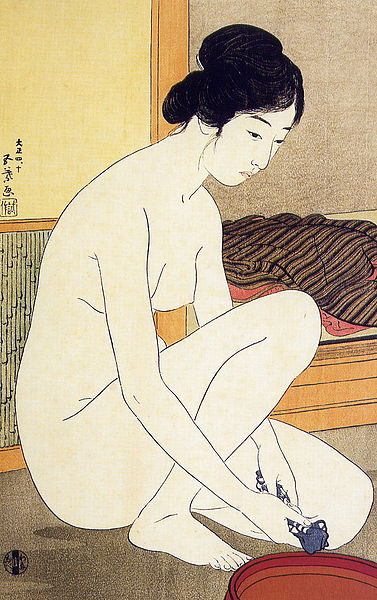

Around this time, Watanabe Shozaburo contacted Hashiguchi, having seen the Mitsukoshi poster. Watanabe, a publisher of ukiyo-e woodblock prints was looking for artists who would push the old methods and style forward into the new era. Hashiguchi thus, in 1915, produced the artwork for the print Bathing, which was carved and printed by one of Watanabe’s assistants. This was the birth of the shin-hanga – new prints – movement.

Around this time, Watanabe Shozaburo contacted Hashiguchi, having seen the Mitsukoshi poster. Watanabe, a publisher of ukiyo-e woodblock prints was looking for artists who would push the old methods and style forward into the new era. Hashiguchi thus, in 1915, produced the artwork for the print Bathing, which was carved and printed by one of Watanabe’s assistants. This was the birth of the shin-hanga – new prints – movement.

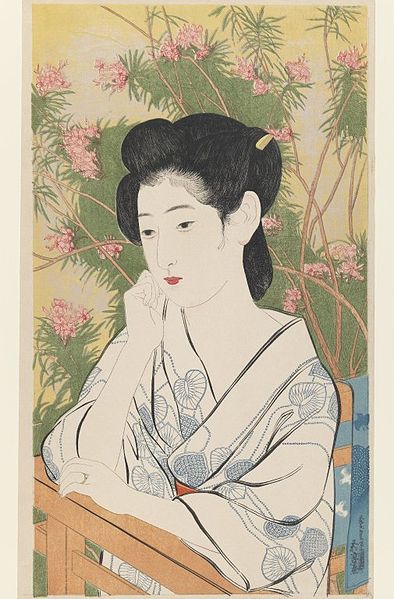

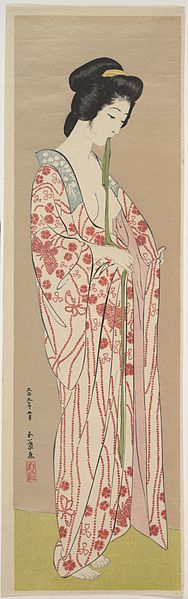

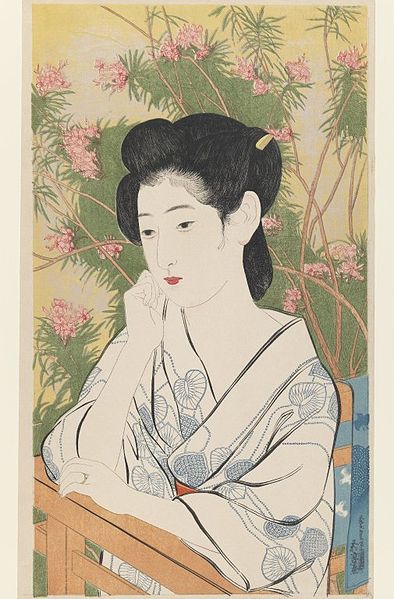

Since this sensitive print was an immediate success, Watanabe wanted to continue the collaboration, but Hashiguchi declined, preferring to work independently. In the years 1916 and 1917, he supervised the production of 12 volumes of “Japanese Color Prints”, containing hundreds of scaled-down reproductions of renowned ukiyo-e artists’ works. During this time, he deepened his knowledge about the printing process, and from 1918, he produced his own prints again. Often, Hashiguchi started with drawings from live models, which he then adapted and refined to make his beautiful woodblock prints.

Since this sensitive print was an immediate success, Watanabe wanted to continue the collaboration, but Hashiguchi declined, preferring to work independently. In the years 1916 and 1917, he supervised the production of 12 volumes of “Japanese Color Prints”, containing hundreds of scaled-down reproductions of renowned ukiyo-e artists’ works. During this time, he deepened his knowledge about the printing process, and from 1918, he produced his own prints again. Often, Hashiguchi started with drawings from live models, which he then adapted and refined to make his beautiful woodblock prints.

Unfortunately, Hashiguchi’s health was quite frail. He suffered from beriberi around 1914, and by late 1920, his latent health problems escalated to meningitis, from which he ultimately did not recover. Nevertheless, he supervised his last print Hot Spring Hotel from his sickbed, but could not see it to completion. He died in February 1921, only 41 years of age. His grave is in his hometown in Kagoshima.

Unfortunately, Hashiguchi’s health was quite frail. He suffered from beriberi around 1914, and by late 1920, his latent health problems escalated to meningitis, from which he ultimately did not recover. Nevertheless, he supervised his last print Hot Spring Hotel from his sickbed, but could not see it to completion. He died in February 1921, only 41 years of age. His grave is in his hometown in Kagoshima.

Because of his untimely death, Hashiguchi’s body of shin-hanga prints comprises only 14 works in total. Besides the single sheet for Watanabe, he produced 1 nature print, 4 landscapes, and 8 more prints of women. Seven more prints that were in various stages of completion at the time of his death were later finished and published by his heirs – his elder brother and nephew – and 10 more prints based on Hashiguchi’s remaining designs were published years later, together with reprints of his original work. These reprints have an additional mark in the margins, which the originals do not have.

Because of his untimely death, Hashiguchi’s body of shin-hanga prints comprises only 14 works in total. Besides the single sheet for Watanabe, he produced 1 nature print, 4 landscapes, and 8 more prints of women. Seven more prints that were in various stages of completion at the time of his death were later finished and published by his heirs – his elder brother and nephew – and 10 more prints based on Hashiguchi’s remaining designs were published years later, together with reprints of his original work. These reprints have an additional mark in the margins, which the originals do not have.

Hashiguchi’s work is characterised by a mastery of technique, owing to his perfectionism. His standards were so high, that many of his editions had print runs of not more than 80 sheets. This led to his prints being technically the best since the late 18th century. Not only the high quality, but also the beautiful, sensitive, and modern designs, reminiscent of art nouveau, made Hashiguchi’s shin hanga extremely popular; from the very beginning, they demanded high prices.

Hashiguchi’s work is characterised by a mastery of technique, owing to his perfectionism. His standards were so high, that many of his editions had print runs of not more than 80 sheets. This led to his prints being technically the best since the late 18th century. Not only the high quality, but also the beautiful, sensitive, and modern designs, reminiscent of art nouveau, made Hashiguchi’s shin hanga extremely popular; from the very beginning, they demanded high prices.

In the 1923 Kanto Earthquake that all but destroyed Tokyo, most of the original printing blocks and prints themselves were destroyed. This makes any original Hashiguchi Goyo prints and sketches extremely valuable and sought after – they can sell for as much as 10.000 $, which makes them among the most highly prized of all shin-hanga.

The main house was built in the Taisho era (about 100 years ago) and was subsequently enlarged. It has an obvious Western feeling to it, but even so, there are many features that are reminiscent of Japanese style: enormous wooden beams (one square one with a side length of 50cm) support the ceilings, and the entrance and second floor have high ceilings where the roof structure can be seen, there are little ornaments featuring bamboos… But mainly, the house is Western style: there are two large terraces on the second floor, together with a very modern looking guest bathroom with beige tiles that even features fixtures for hot water. The ground floor sports a large dining room and parlour with enormous fireplace, and out into the back, there is an airy corridor with lots of windows that once led to a greenhouse for orchids.

The main house was built in the Taisho era (about 100 years ago) and was subsequently enlarged. It has an obvious Western feeling to it, but even so, there are many features that are reminiscent of Japanese style: enormous wooden beams (one square one with a side length of 50cm) support the ceilings, and the entrance and second floor have high ceilings where the roof structure can be seen, there are little ornaments featuring bamboos… But mainly, the house is Western style: there are two large terraces on the second floor, together with a very modern looking guest bathroom with beige tiles that even features fixtures for hot water. The ground floor sports a large dining room and parlour with enormous fireplace, and out into the back, there is an airy corridor with lots of windows that once led to a greenhouse for orchids.

Rakugo goes back to Buddhist monks of the 10th century, who interjected little, often humorous stories to their sermons to make them better understandable for the lay people. The stories evolved to a kind of monologue that people told among themselves, and especially the daimyo of the Edo period were the patrons of this kind of storytelling. With the rise of the rich merchant class, however, rakugo as an art form finally spread to the common people, and by the end of the 18th century, professional rakugoka had emerged, who rented rooms – yose – for their performances. Finally, theaters especially for rakugo were set up as well.

Rakugo goes back to Buddhist monks of the 10th century, who interjected little, often humorous stories to their sermons to make them better understandable for the lay people. The stories evolved to a kind of monologue that people told among themselves, and especially the daimyo of the Edo period were the patrons of this kind of storytelling. With the rise of the rich merchant class, however, rakugo as an art form finally spread to the common people, and by the end of the 18th century, professional rakugoka had emerged, who rented rooms – yose – for their performances. Finally, theaters especially for rakugo were set up as well.