Umenomiya Taisha is a rather small shrine with a very large garden tucked away in a residential area in Arashiyama. It was founded about 1300 years ago by Agata Inukai no Michiyo (or Tachibana Michiyo) as a shrine for her ancestors, in a little place in the rural parts of Kyoto prefecture. With the rise of the Tachibana family into imperial ranks, the shrine was moved twice before it was relocated to Kyoto around the year 800 to the place where it still stands today.

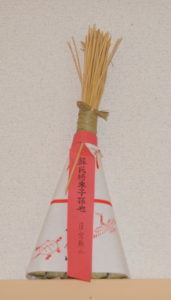

Umenomiya Taisha enshrines the mountain god Oyamazumi-no-kami and his daughter Konohana-no-sakuyahime, the goddess of life. Legend says, that Oyamazumi-no-kami was so pleased when his daughter gave birth to his first grandson, that he invented sake to celebrate the occasion. Furthermore, it is said that her delivery took place one day after her marriage, and it was a quick and easy one. For these reasons, the shrine is still popular with sake brewers and couples hoping for children.

Umenomiya Taisha enshrines the mountain god Oyamazumi-no-kami and his daughter Konohana-no-sakuyahime, the goddess of life. Legend says, that Oyamazumi-no-kami was so pleased when his daughter gave birth to his first grandson, that he invented sake to celebrate the occasion. Furthermore, it is said that her delivery took place one day after her marriage, and it was a quick and easy one. For these reasons, the shrine is still popular with sake brewers and couples hoping for children.

The main entrance of the shrine is through the red torii and the two storey Romon gate in the south. The two zuishin warriors placed inside the gate are rather common; the special feature are the rows of sake barrels stacked on the second floor.

Directly behind the Romon gate lies the haiden dance stage. Just like the gate, it was rebuilt in 1828 and is a Kyoto prefecture registered cultural property. To the right of the Romon gate, there is a large and interesting pine tree whose stem has been twisted around itself by the gardeners. I don’t know how old it is, but it does look very impressive.

Directly behind the Romon gate lies the haiden dance stage. Just like the gate, it was rebuilt in 1828 and is a Kyoto prefecture registered cultural property. To the right of the Romon gate, there is a large and interesting pine tree whose stem has been twisted around itself by the gardeners. I don’t know how old it is, but it does look very impressive.

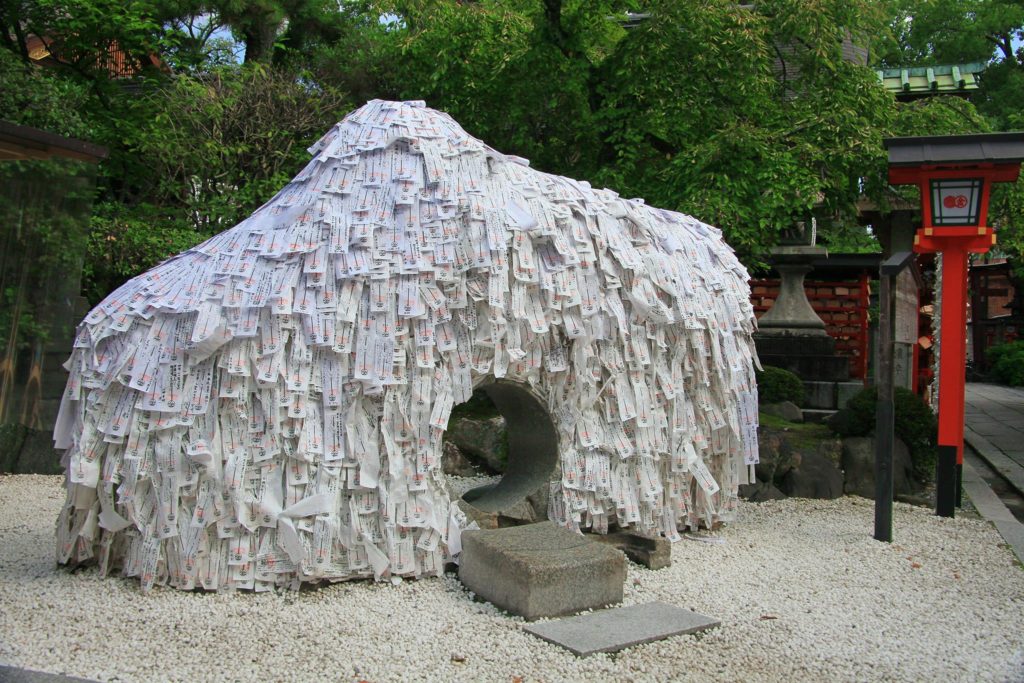

The honden prayer hall at the very north dates from 1700 and is the oldest building of the shrine, with a beautiful cypress-bark roof. Beyond the honden, surrounded by ancient trees, lies the actual sanctuaries of the gods. Also back there, and not generally accessible, lie the Matage-ishi stones, that come with the following legend: Empress Danrin, who had moved the shrine to Kyoto, had difficulties conceiving until she came to Umenomiya Taisha and stepped over the stones, upon which she was immediately blessed with a son. The story goes further that she took sand from the shrine and spread it under her bed, aiding in an easy delivery. To this day, many couples who want children come to the shrine to perform the Matage-ishi ceremony, and some of the shrine’s omamori talismans allegedly contain sand surrounding the Matage-ishi stones.

The honden prayer hall at the very north dates from 1700 and is the oldest building of the shrine, with a beautiful cypress-bark roof. Beyond the honden, surrounded by ancient trees, lies the actual sanctuaries of the gods. Also back there, and not generally accessible, lie the Matage-ishi stones, that come with the following legend: Empress Danrin, who had moved the shrine to Kyoto, had difficulties conceiving until she came to Umenomiya Taisha and stepped over the stones, upon which she was immediately blessed with a son. The story goes further that she took sand from the shrine and spread it under her bed, aiding in an easy delivery. To this day, many couples who want children come to the shrine to perform the Matage-ishi ceremony, and some of the shrine’s omamori talismans allegedly contain sand surrounding the Matage-ishi stones.

Umenomiya Taisha has a large garden that can be entered through the Higashi Mon, the eastern gate. It looks less perfectly laid out as some of the other shrine gardens, but the slightly unkempt appearance has a lovely charm to it that is worth experiencing. The so-called Shin-en gardens contain two ponds: Directly behind the gate, in the east gardens, lies Sakuya Ike, where different types of Iris and lotus greet the visitors. Inside the pond, that is teeming with colourful carp, is an island with the little tea house Ikenaka-tei, built in 1852 by wealthy Minamoto-no-Morokata who lived in the area.

Further along the path, in the north garden, lies Magatama Ike. It has the shape of a comma, resembling the ancient magatama jewels made from jade. Again, it is filled with Iris and lotus flowers, and surrounded by plum and cherry trees. There is no prominent pond in the west garden, but instead, there are many little paths among colourful hydrangea bushes and peaceful trees.

Further along the path, in the north garden, lies Magatama Ike. It has the shape of a comma, resembling the ancient magatama jewels made from jade. Again, it is filled with Iris and lotus flowers, and surrounded by plum and cherry trees. There is no prominent pond in the west garden, but instead, there are many little paths among colourful hydrangea bushes and peaceful trees.

The best time to visit the gardens is in the first half of the year, where different flowers mark the passage of time, starting with plums and cherries, iris and lotus flowers and azaleas and hydrangeas. Spring is especially lovely when the 500 plum trees of 40 varieties in different colors from bright white to dark crimson are in bloom. Although less interesting in summer and autumn, the west garden has many hidden paths with quiet benches, where you can sit in the shade and enjoy the solitude.

The best time to visit the gardens is in the first half of the year, where different flowers mark the passage of time, starting with plums and cherries, iris and lotus flowers and azaleas and hydrangeas. Spring is especially lovely when the 500 plum trees of 40 varieties in different colors from bright white to dark crimson are in bloom. Although less interesting in summer and autumn, the west garden has many hidden paths with quiet benches, where you can sit in the shade and enjoy the solitude.

Umenomiya Taisha is a hidden gem worth visiting for all those who like to venture off the beaten tracks. It should also be on the list for cat lovers since the family of the shrine’s priest is taking care of a large colony of very photogenic cats. They seem to be very popular with even renowned photographers, and there are postcards of the cats for sale at the shrine. Yet more unconventional shrine souvenirs are umeboshi, pickled plums, made from the very plums that grow in the gardens, or a bottle of sake that is specially made for the shrine – although probably not by the gods any more.

They are nice, with a very rich chocolate taste, so there will be more to come even though they are pretty small. The one thing I don’t understand is the Tirol connection. Especially since most Japanese wouldn’t know the name – the only two places they know about Austria are Vienna and Salzburg. But I guess it’s just like with so many things used for advertising in Japan – as long as they look and sound cool, anything goes…

They are nice, with a very rich chocolate taste, so there will be more to come even though they are pretty small. The one thing I don’t understand is the Tirol connection. Especially since most Japanese wouldn’t know the name – the only two places they know about Austria are Vienna and Salzburg. But I guess it’s just like with so many things used for advertising in Japan – as long as they look and sound cool, anything goes…