Shibori is the Japanese method of tie-dyeing, a type of resist dyeing where parts of the fabric are prepared (in this case: tightly tied with thread) before dyeing so that the tied parts of the fabric remain the original color.

Shibori, or rather: tie-dyeing or resist dyeing methods have sprung up all over the world and can be traced back to as early as the 2nd century. Simple methods of resist dyeing meant simply crumpling up the cloth before dyeing, but methods have evolved to include the use of wax or stencils etc. Tie-dyeing came to Japan from China in the 7th century and has been refined to create the art of shibori.

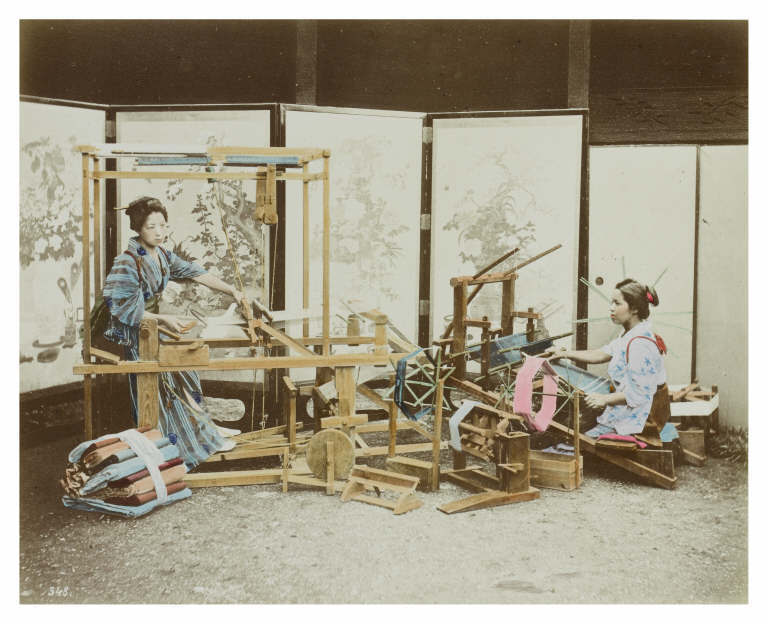

Shibori with its tiny and delicate patterns reached its peak in the Edo period, where shibori fabric was produced in many places of Japan. Especially farmers would work in the shibori industry – meaning: binding the cloth – during the off-season when there was not much work to do on the farm. Unfortunately, nowadays, shibori is only produced in Nagoya and Kyoto, and because it is still largely a very time-consuming handicraft, the number of craftsmen and -women who can do it is declining.

Shibori comes in many different forms, depending on the way the fabric is tied. The most delicate type of binding the fabric is called hon-hitta shibori, the finished tied beads are only 2mm in size; this is entirely handmade and an experienced craftsperson can make around 300 of these beads per day.

This was the standard type of shibori before the machine-type hari-bitta shibori was introduced, “machine” being simply a metal holder with a needle to help pinching the fabric before tying it. While the process is still a handicraft, this tool has sped up production to about 3000 beads per day.

Other methods that fall under the shibori umbrella are tie-dyeing with larger objects like plugs made from wood or acrylic; using wooden boards like a stencil; sewing patterns into the fabric with strong thread etc. Probably the most interesting one is where the cloth is placed carefully in and outside of a wooden tub, the parts inside the tub remain white while the ones outside will be dyed in the respective color. This so-called oke-shibori technique can produce very striking, large-scale patterns.

Other methods that fall under the shibori umbrella are tie-dyeing with larger objects like plugs made from wood or acrylic; using wooden boards like a stencil; sewing patterns into the fabric with strong thread etc. Probably the most interesting one is where the cloth is placed carefully in and outside of a wooden tub, the parts inside the tub remain white while the ones outside will be dyed in the respective color. This so-called oke-shibori technique can produce very striking, large-scale patterns.

The shibori process is very involved and takes a number of steps, each of which is carried out by a specialist. First, a pattern is created and from it, a stencil is made. Using the stencil and a special type of water-soluble dye, the pattern is transferred to the fabric. Then, the fabric is tied according to the pattern. If there are different types of shibori to be included, each one is given to a specialist in the respective type of binding. However, no matter how large the piece is, one type of binding is always given to a single craftsperson because to achieve a uniform appearance in the final piece, the strength of the binding must be the same throughout.

The shibori process is very involved and takes a number of steps, each of which is carried out by a specialist. First, a pattern is created and from it, a stencil is made. Using the stencil and a special type of water-soluble dye, the pattern is transferred to the fabric. Then, the fabric is tied according to the pattern. If there are different types of shibori to be included, each one is given to a specialist in the respective type of binding. However, no matter how large the piece is, one type of binding is always given to a single craftsperson because to achieve a uniform appearance in the final piece, the strength of the binding must be the same throughout.

Once all the fabric is tied it is called a shirome and now it is given to the person who is actually dyeing it. Again, this is a handicraft, and the color depends on factors like the type and heat of the dye and the amount of time the fabric stays in it. Only after the piece is completely dry will the fabric be unbound (again by an expert) and afterwards, it will be steamed to make it flat. With this method, a finished piece of shibori will never be completely flat but will retain a bit of a 3D structure, which is the hallmark of good shibori.

As mentioned above, nowadays shibori is only produced in Nagoya and in Kyoto (and a few surrounding places). Nagoya shibori is made on various materials including cotton, but the kyo kanoko shibori of Kyoto only uses silk fabric. Because of the fact that they are still handmade, shibori items are rather expensive, but it does depend on the pattern and the dyeing. The more intricate the pattern, the more colors, the more expensive. Still, given that a whole kimono done in hon-hitta shibori can have up to 200,000 of little tied beads and can take years to complete, the prices are understandable.

As mentioned above, nowadays shibori is only produced in Nagoya and in Kyoto (and a few surrounding places). Nagoya shibori is made on various materials including cotton, but the kyo kanoko shibori of Kyoto only uses silk fabric. Because of the fact that they are still handmade, shibori items are rather expensive, but it does depend on the pattern and the dyeing. The more intricate the pattern, the more colors, the more expensive. Still, given that a whole kimono done in hon-hitta shibori can have up to 200,000 of little tied beads and can take years to complete, the prices are understandable. For more information on shibori, visit the Kyoto Shibori Museum. Their exhibits are stunning and they also offer short classes to make your own (simple) shibori piece.

For more information on shibori, visit the Kyoto Shibori Museum. Their exhibits are stunning and they also offer short classes to make your own (simple) shibori piece.