Last Friday, I was invited to the press preview of the 118th Nitten, one if not the largest exhibition of contemporary Japanese artists. It is a touring exhibition where each stop features about 50% local artists, in this case from Kyoto and Shiga prefectures.

The Nitten comprises five art faculties; namely Japanese Style and Western Style Painting, Sculpture, Craft as Art and Calligraphy. Each of the departments features works of the great masters of the modern Japanese art world alongside the works of new talents. At the press preview, each section was introduced by one of those great masters (I believe) but since the whole preview was limited to one hour, there was not enough time to really appreciate the whole exhibition.

In any case, here are a few of my personal favourites from this Nitten exhibition.

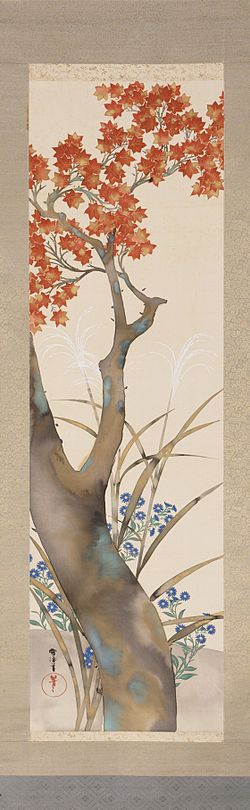

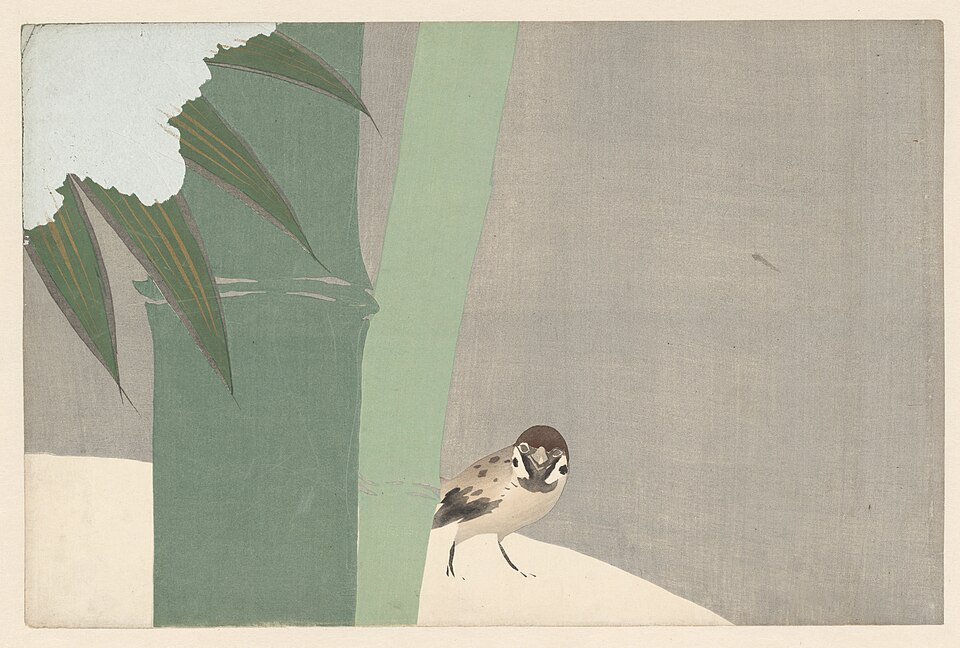

This one is a nihonga – Japanese painting called “Ray of Light”, and on closer inspection it’s red leaves in a forest.

This one is another nihonga, it looks quite abstract on first glance, but it isn’t. I would call it wabi-sabi.

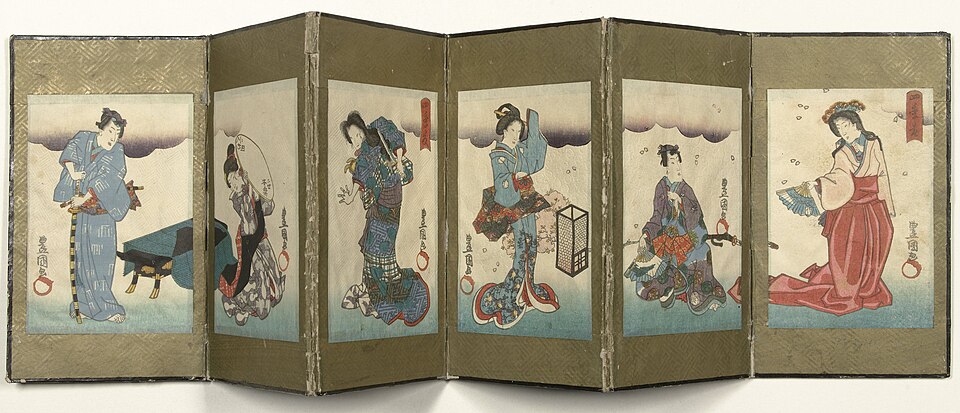

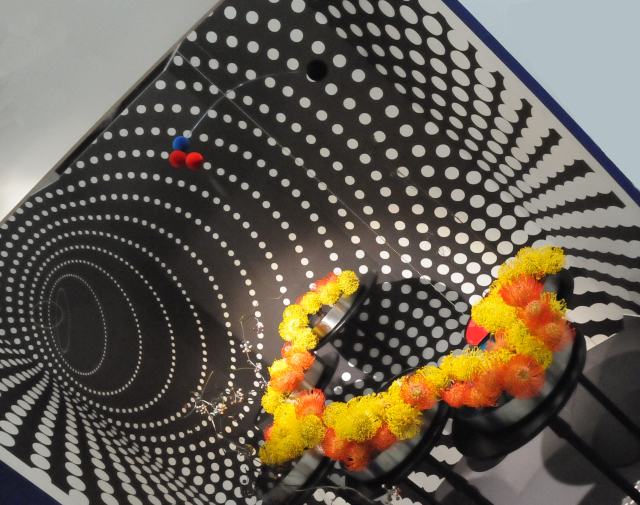

The next images are from the “Crafts as Arts” section. My favourites were the lacquer pieces, but thanks to their shiny black surface they are incredibly difficult to photograph. Hence just an overview. The pieces on the wall are not paintings, but textiles, either woven or in yuzen-dyeing.

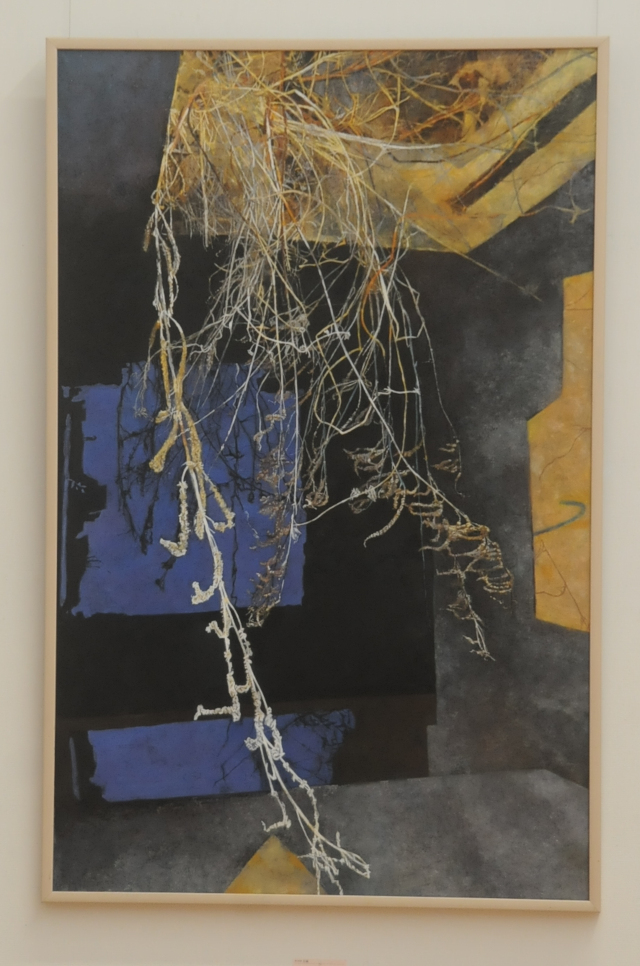

My favourite part are always the sculptures. I remember the very first Nitten I want to, where about 90% of the exhibits were nude females standing like soldiers, looking straight ahead. I was so disappointed – what a waste of medium! However, things have improved considerably as you can see, I wonder if the people who choose the art have changed.

This was my favourite piece of the whole exhibition. She looks defiant and confident in herself, yet sensual at the same time. As with most of the art that I like I can’t really say why exacly I like her. Apparently the piece is called “Dusk”.

And here are yoga, Western-style paintings. Tokyo Tower stood out to me, a bustling evening scene in the big city with bright colors and lights everywhere.

And here is Ojii-san, he comes every year to the exhibition and brings his grandchildren. They are growing up! With the horses in the background, it’s probably a nod to 2026, the Year of the Horse. I’ll have to check the other paintings if there’s a similar theme.

That was the Nitten, the last big exhibition for me this year. This is also the last post before I go on my annual Christmas holiday; I’ll be back on January 7th next year or thereabouts.