Japanese is rather difficult to learn for people who speak a Western language. Part of the difficulty lies in its three distinct scripts for writing (actually it’s four if you include romaji, the Latin alphabet, which is also used):

All of these three, which I will talk about the next few weekends, are freely mixed together in sentences, and although there are some rules when to use which scipt, those can be bent to express slight nuances. While you shouldn’t expect to be able to read everything you may encounter without extensive study, knowing how to decipher some word here and there may come handy. Let’s start with the the script that is – at least in my opinion – easiest to learn:

Hiragana

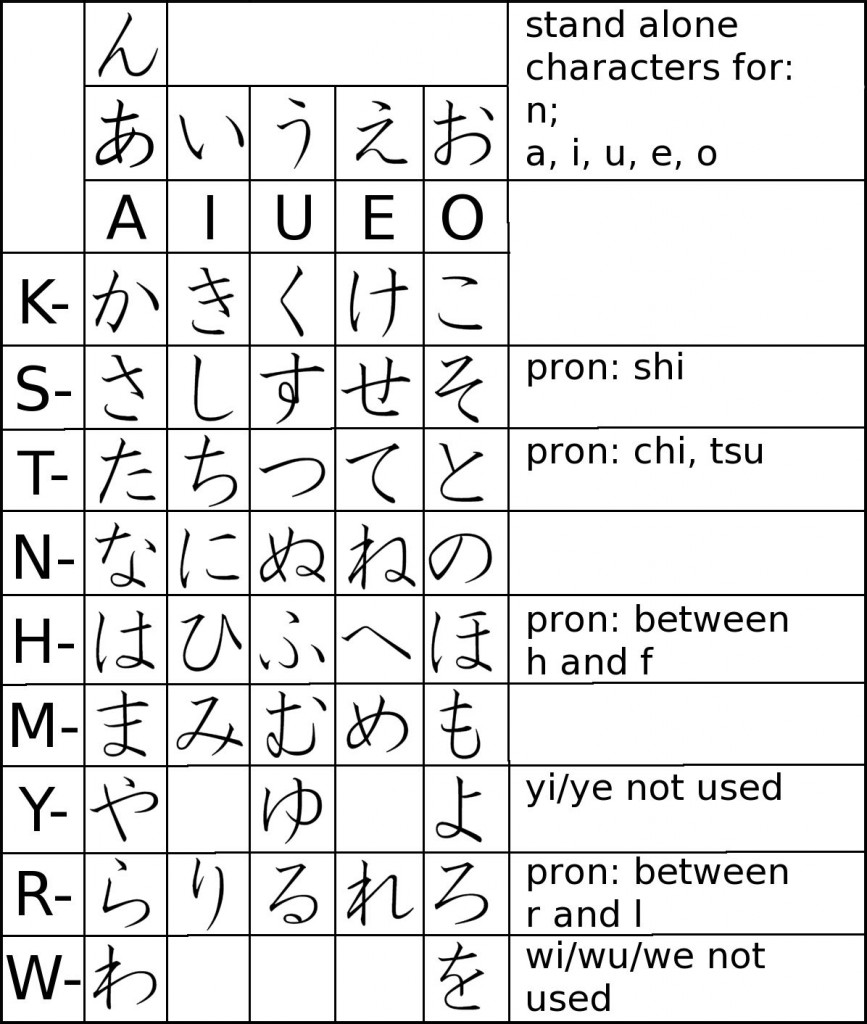

Hiragana is one of the two Kana scripts used in Japan. It consists of 46 basic characters, 40 of them are syllables (always consonant + vowel), 5 of them are the single vowels A, E, I, O, U (pronounced like in Latin or Spanish, btw), and there is a single symbol for the consonant N. Here is a list of them (empty squares mean they are no longer in use):

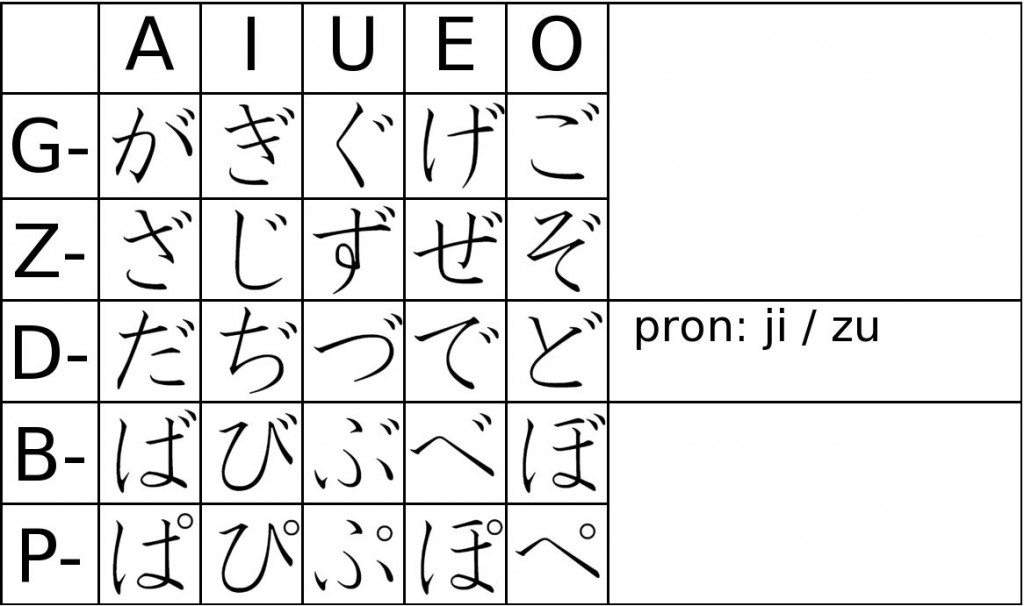

Additionally, some diacritic marks are used to add some more consonants:

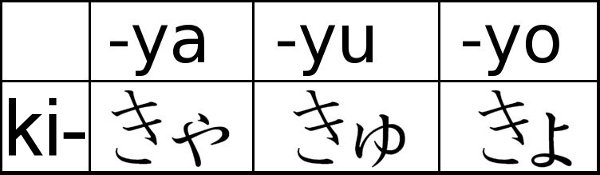

and then there are syllables for kya, dyo, … etc. (note that the second part is written slightly smaller)

and doubling of consonants are indicated by adding a slightly smaller tsu before the consonant (exception: N, where you simply add the symbol for N).

That does not appear that difficult after all, does it? So, when is Hiragana used?

Hiragana characters are mainly used for:

- any Japanese words for which there are no Kanji or where the Kanji are obscure (Japanese could be completely written in Hiragana, and in fact, all children’s books are)

- grammatical elements like verb and adjective inflections (called okurigana), particles, and suffixes.

- so called furigana, indicating the pronunciation of Kanji, mostly seen in books for children as sub- or superscripts to the Kanji they describe (or in parentheses behind them)

Hiragana have developed from Kanji, and were long considered “women’s writing” when women were not allowed to study the Chinese Kanji. Many works of early Japanese literature have been written in Hiragana, for example the famous “Tale of Genji” by Murasaki Shikibu, or “The Tosa Diary” by Ki No Tsurayuki (a man who pretends to a woman writing the diary). Even today, Hiragana are used instead of Kanji when a non-formal way of writing is desired, or when trying to convey a more warm feeling.