On Friday, I went to this year’s Autumn Tanabata Exhibition of the Ikenobo school for ikebana flower arranging. This is the oldest annual exhibition of ikebana; it dates back to the Edo period and has been ongoing ever since. I have written about the history of ikebana and the Ikenobo school when I went to the spring exhibition in 2022, so I will not go into details again here.

This year, I had as a guide a friend of mine who works at the Ikenobo to show me through the exhibition and explain more of the art behind ikebana and what to look for in an arrangement. Here are a few details of what she told me.

Rikka is the oldest, most traditional style of flower arrangement and the most heavily formalized. It originated in the Muromachi era and was meant for large-scale arrangements in temples and the homes of nobles and samurai – essentially to show off their wealth and influence.

In Rikka, the goal is to create a whole landscape with a wide variety of plants; the back and top of the arrangement signifies the landscape far off, the closer and lower parts the nature nearby. Rikka is easily recognized by the round bundle the stems of the plants form in the container.

Shoka was developed in the Edo period. These arrangements are often much smaller, since they were meant for the tokonoma in the rooms of the lower class people (albeit rich ones, think merchants etc.)

A Shoka arrangement uses at most three different types of plants, they form a single line segment in the container and are best viewed from the front of the row rather than the side. Shoka is considered the most dignified style, and ideally, the flowers used encompass the past, present, and future of the seasons.

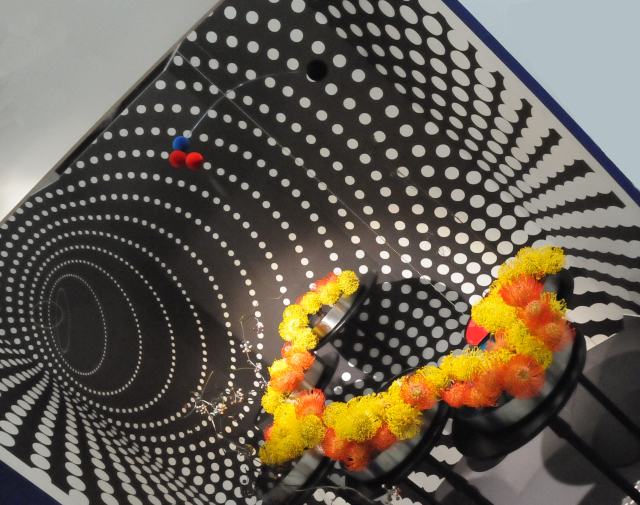

Then there is Free Style, where essentially “anything goes”. These arrangements come in all sizes and often include non-natural materials as well. Looking through the photos I took, I find myself mostly drawn to these pieces, they are very individual and often outright whimsical. Yet, the flowers should still form the focal point of the arrangement.

The goal of any arrangement in any style is that it looks as natural as possible, even if artificial means are used. We’re talking about using wires to bend stiff materials, or hand creme to prevent the tips of leaves from drying out too quickly. Some arrangements are even planned out in advance, and tree branches are cut and put together to create specific angles to fit the design. All of this is fine – as long as the end result still looks natural.

When learning ikebana in the Ikenobo school, students start out with the Free Style before moving on to Shoka and finally, Rikka. My friend explained that soft materials are easiest to use, while a Rikka arrangement that only consists of pine branches, for example, marks the height of a student’s accomplishment.

With all this information, the exhibition was much more enjoyable than the previous time. I feel I know some details to look for, even though I cannot judge the actual artistic merit of an arrangement. So far, I’ve always thought that ikebana had very strict rules to create a piece, but when starting out in Free Style, this is not necessarily true. I’m thinking it might be nice to try ikebana, but it is a very expensive hobby indeed.