A very short recap of a very perfect weekend:

Pumpkin and I had our very first overnight visitor! Because it’s Gion Matsuri and Kyoto is practically booked solid, my friend from Tokyo stayed in our guest room – aka upstairs living room. Pumpkin was not very happy about this; he oscillated between anxiety and curiosity. Both of which meant that he was up all night, keeping me the same…

She came down to finally get to the bottom of my BATI-HOLIC obsession and went to their 20th Anniversary concert with me. Well, let’s just say she isn’t into rock music. Which is fine; I’m happy that she at least tried. The photo of lead singer Nakajima is courtesy of my friend, just before she left to have dinner. I had an absolute blast for more than 2 hours, met some old friends and made some new ones… As I said: PERFECT!

Anyway, I am sure you’re pretty tired of my fangirling here already, so I’ll stop… In case you’re not, I wrote an article about 20 Years of BATI-HOLIC for my WUIK newsletter, which actually made it into a (rock) music magazine in Australia of all places. You can read my article in the Heavy Magazine.

After sleeping in and having a relaxed breakfast, my friend and I went to Shisendo, a nearby temple that is always pretty quiet. The gardens are nice, but not spectacular (outside the azalea season that is), but it is a nice place to sit for a while.

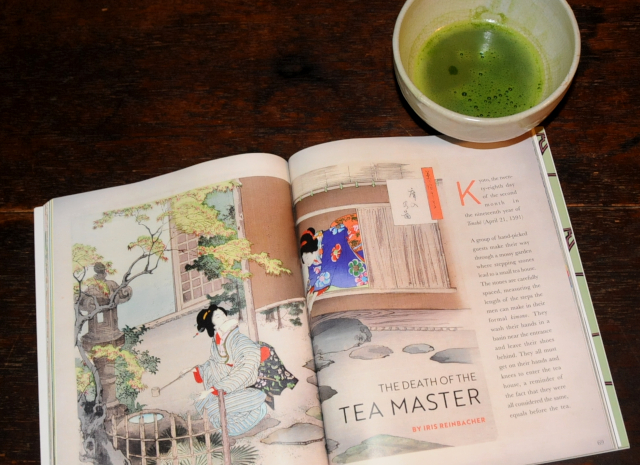

In the afternoon, we went to the Insho Domoto Museum, a favourite of mine; their current exhibition is about monochrome ink paintings, and my favourite painting is exhibited as well. I still can’t describe why it makes me feel the way I feel, but it still moves me to tears every time I see it. My friend was quite put out (and not as impressed about this particular painting I might add.)

Anyway, my friend is back in Tokyo, I’m back at home, Pumpkin is back at ease – and at least I had the perfect weekend! Tomorrow is a holiday to boot, so I can sleep in again. I’m very happy!