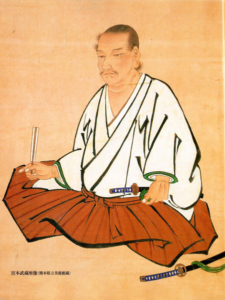

Shinzō Abe, former Prime Minister of Japan, was assassinated last Friday during an election campaign speech in Nara. He was born in 1954 into a family that served as politicians, and he himself entered the political scene in the 1990s. For four terms, he served as prime minister, until he retired for health reasons in 2020. Yet, he remained an eminent figure in the background and still had considerable influence over his party and thus, the country.

His assassination shocked the country. There is a video out there, showing him on a street corner in Nara at around 11:30, giving a speech. Suddenly, from nearby, shots are fired (you can see the smoke), and Abe falls, obviously hit. He was pronounced dead in the hospital at around 17:00.

What’s so shocking is, that Japan has extremely strict gun laws. It is very difficult and can take years to get a gun licence, and in fact, the assassin had to make his own gun. Last year, in 2021, there were only 10 incidents with guns; 8 of them were related to the yakuza (organized crime) and only one of them was fatal. Interestingly, assassinating Japanese politicians seems not to be unusual. In 2007, the mayor of Nagasaki was shot during an electoral campaign, and in 2002, a member of the Democratic Party of Japan was assassinated. The assassinations of the last prime ministers, however, date back to the February 26 Incident in 1936, when two former prime ministers were killed.

I found it especially disturbing how close the murderer could get to Abe. Watching the video I mentioned, they were within a few meters of each other; Abe had his back turned. Yes, Japan is a very safe country and violent crimes outside the yakuza are rare. Yet, I found security sorely lacking. Would Abe be still alive if the assassin had only had a knife? I’m not so sure.

I’m also curious about the ramifications on the country. Clearly, Shinzō Abe’s politics have shaped the country for 15 years, if not twice as long. The void he leaves will have to be filled one way or the other. But how this will happen, we’ll just have to wait and see.