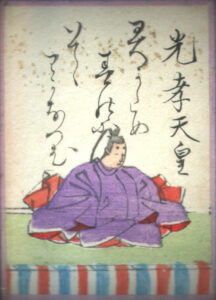

For you,

I came out to the fields

to pick the first spring greens.

All the while, on my sleeves

a light snow falling.

Emperor Koko, 9th cent.

This is a poem from the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu, probably the most famous of all collections of Japanese poetry. The name can be translated as “One hundred people, one poem each” and this anthology of waka poetry was collected in Kyoto’s Arashiyama district. There, at Mt. Ogura, was the home of Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241), himself considered one of Japan’s greatest poets.

He selected many poems by his contemporaries, but also by famous older poets whose work had been handed down for many years, among them 20 women. While there are many other anthologies of waka poetry, it is believed that this one became so famous because of the fame of Fujiwara no Teika – and because he had just the right connections to the Imperial court.

Writing waka poetry was one of the courtiers’ favourite pastimes, and to this day, the emperor himself gives out the prize for the best new year’s poetry. Most of the poems contained in the Hyakunin Isshu are love poems, and many of them allude to a time of the year using words like “cherry blossoms”, “full moon”, “crimson mountains” and others.

The poems and their writers have garnered lots of attention over the years; both feature prominently in woodblock prints or are alluded to in other Japanese works of literature. Since the Edo period, they also have a connection to the New Year in the form of the karuta game.

Karuta is a game of memory, where, when hearing the first half of a poem, the players must find the card with the second half as quickly as possible. There are karuta clubs throughout the country, and therefore, the poems of the Hyakunin Isshu are known by practically every Japanese. At home, it’s usually played as a team of three people – one who reads the beginning of the poem, and two who are trying to find the other half of the card as quickly as possible.

Since 1904, there is also competitive karuta, with the main tournament being held at Omi shrine in January, and roughly 50 other tournaments being held throughout the year. In Japan, there are more than 10,000 competitive players, and the game is even considered a sport.

The Hyakunin Isshu has been translated numerous times into a number of languages. Each translation brings a new aspect to the poetry, yet, there are many hidden meanings that are not only hard to translate, but may fly over the head of the unsuspecting foreign reader. For example, would you have guessed that the “first spring greens” in the above poem (translated by Peter MacMillan) are the nanakusa – seven herbs that are gathered and eaten on January 7 for a healthy winter?