Since its founding, Kyoto has been a hotbed for artists and craftspeople, and not even the move of the government to Tokyo could change that. While Kyoto’s number one craft remains the textile industry, numerous other artists have found a welcoming home here.

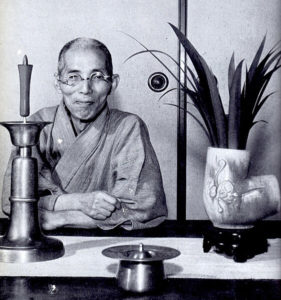

One of these was Kawai Kanjiro, one of the best-known ceramic artists from Kyoto. Although, technically, he is not a Kyoto person, since he was born in Shimane prefecture and only moved to the city after graduating. However, he lived and worked the rest of his life in Kyoto’s Gojozaka area, where he established his pottery workshop and rose to international fame. But let’s start at the beginning of his career.

Already at age 16, Kanjiro decided to become a potter and started to pursue this career. After having graduated from the Department of Ceramic Industry of what is now known as the Tokyo Institute of Technology, he moved to Kyoto to study at the Ceramic Research Institute and there acquired the scientific, chemical basics of making pottery.

However, the purely academic-theoretical approach did not satisfy him, so he taught himself the use of natural glazes and traditional methods used in Japan, China, and Korea. When he was 30, he bought a climbing kiln – a noborigama – at Gojozaka and put his knowledge into action in what is now known as his first period.

Yet, he was still not satisfied and felt that something was missing. Together with Yanagi Soetsu and Hamada Shoji, he founded the Mingei movement, a kind of back-to-the-roots of Japanese folk art, complete with Folk Crafts Museum in Tokyo (established in 1936). This second period is marked by pieces that are reminiscent of Japanese folk art – not just in design, but also in technique.

At this time, Kanjiro also began to write poetry and essays and started to experiment with other forms of expression. After WWII, in what became his third period, he also taught himself wood carving techniques. A number of large-scale pieces survived and they are marked by a shift towards more abstract designs.

Although Kawai Kanjiro soon became well-known in Japan and even abroad, he was not interested in personal fame. He rarely signed his pieces, noting that his style should speak for itself; he also eschewed taking part in prize events. The two Grand Prix Prizes at international exhibitions he received were due to friends submitting his pieces. Kanjiro also declined many honors of the Japanese government, like being named a “Living National Treasure”, which is one of the highest distinctions for Japanese artists.

Kawai Kanjiro died in 1966, but his adopted heir Hirotsugu, as well as his nephew Takeichi and his son Toru continued the family tradition of mingei pottery.

The former residence and workshop of Kawai Kanjiro, located in the Gojozaka neighborhood, the traditional potter’s district of Kyoto, opened as a museum in 1973. It was designed and remodeled by Kawai Kanjiro himself in 1937 and differs from the many machiya merchant houses of Kyoto in important ways. First of all, it was modeled after classical rural cottages rather than urban town houses, additionally, it shows some Western influences. The large room near the entrance, for example, has a wooden floor on one side and slightly raised tatami on the other, with a traditional irori sunken hearth as the centerpiece.

The house is quite large, and most of the rooms are accessible. At the rear of the house lies Kawai’s workshop where he created his pottery together with his son and apprentices. Also preserved and accessible is the large noborigama climbing kiln that has eight chambers and was built on/into the slope behind the house.