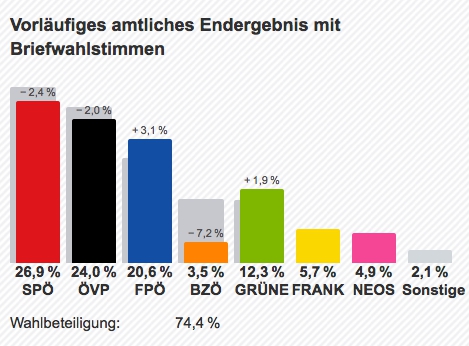

Yesterday the elections for the Austrian parliament took place. Of course I did my bit, actually about two weeks ago already as the laws had changed and my vote needed to arrive in Austria yesterday already (maybe somebody needs another explanation of the meaning of “date of postmark”). Anyway, here are the results:  I’m not happy about this at all – too many votes for the right wing, although I am glad that there’s now only one of those parties in the parliament (Austria has a proportional representation with a 4% lower limit for entering the national assembly). Unfortunately the result seems to imply the same old people in the same old positions with the same old ideas… I’m not sure if it could be worse, actually.

I’m not happy about this at all – too many votes for the right wing, although I am glad that there’s now only one of those parties in the parliament (Austria has a proportional representation with a 4% lower limit for entering the national assembly). Unfortunately the result seems to imply the same old people in the same old positions with the same old ideas… I’m not sure if it could be worse, actually.

Haori

I have to admit that in my Wednesday post about the flea market, I committed the sin of omission. The soroban (which I have put to good use for the first time in today’s class) was not my only purchase. I also bought a haori.

A haori is a kimono jacket that can be as short as waist length but usually goes down to about mid-thigh. Traditionally, it was made in black silk with white family crests on the back and the sleeves, and was worn by men only, together with their standard outfit of kimono and hakama. With the big changes in the Meiji period, however, they became fashionable for women also, albeit in much more fancy colours. I have heard that haori were often made by simply cutting off an old kimono and thus removing damaged parts, for example at the hem. As a haori is a jacket, it is not meant to close in front as a kimono, but is merely held together by two simple ties called haori-himo. The black, most formal haori for men are held together with white haori-himo with a big, feathery tassel in the middle.

Above is a picture of my brand new second hand haori, made of red silk with a somewhat geometric pattern (yeah, the nerd in me…) and with white lining and long sleeves. It is beautiful, and I hope that it is rather warm as well – it is surprisingly heavy, after all.

Above is a picture of my brand new second hand haori, made of red silk with a somewhat geometric pattern (yeah, the nerd in me…) and with white lining and long sleeves. It is beautiful, and I hope that it is rather warm as well – it is surprisingly heavy, after all.

Metering

Any Japanese house or apartment has a meter for electricity, gas, and water. Different to Europe, where you get the bill once a year and you pay a monthly amount based on your average monthly usage of the last year; here, the meters are read each month and you pay what you have actually used. Personally I prefer this system, it gives you more control I think and it is easier to find out whether there is a leak somewhere, for example.

Each company ha s numerous employees that go to each house and read the meters. Usually they just enter the genkan entrance area (Japanese homes are rarely locked during daytime) and loudly announce their presence. They then are allowed inside to read the respective meters, sometimes leave a note with the current reading, and are off again. A few days later the bill will arrive. I am not entirely sure how it is here, but often the bill does not even bear a name, only the address – which makes for one less thing to remember when moving in or out… When nobody is home, a note is left requesting somebody of the household to read the meter and phone the company. I don’t think, however, that anybody in this house has ever done so, I guess in such a case the company simply waits for the next opportunity.

s numerous employees that go to each house and read the meters. Usually they just enter the genkan entrance area (Japanese homes are rarely locked during daytime) and loudly announce their presence. They then are allowed inside to read the respective meters, sometimes leave a note with the current reading, and are off again. A few days later the bill will arrive. I am not entirely sure how it is here, but often the bill does not even bear a name, only the address – which makes for one less thing to remember when moving in or out… When nobody is home, a note is left requesting somebody of the household to read the meter and phone the company. I don’t think, however, that anybody in this house has ever done so, I guess in such a case the company simply waits for the next opportunity.

More modern houses than ours may have their meters in more accessible spots outside, so that entering the house is not required anymore. I have seen meters nicely hidden behind little wooden doors or holes made into fences, just large enough for the numbers to be read. Still, not all of the outside meters are placed in a straightforward manner. Our neighbour’s, for example, is mounted on a spot that is about three meters above street level – there is no way to read the numbers from there. When I first realized this, I expected some very ingenious, possibly wireless, transfer of the meter reading going on, after all, this is a highly industrialized nation! Imagine my surprise when last week, I finally caught the woman doing the reading at our neighbour’s – with very small and rather untechnological – binoculars…

Flea Market

Every month on the 25th, the big flea market at Kitano Tenman-gu shrine takes place. As I wanted to look for something particular, and the weather was just perfect today, I went there in the morning.

Kitano Tenman-gu’s market is a typical flea market. From the first torii gate back to the shrine buildings there are food stalls, toys and games for kids, and also newly made handicraft. You can also buy fruits and veggies there, and one part is dedicated to flowers, plants, bushes – and bonsai. In the eastern part of the grounds, however, there is the “real” flea market, where people sell things second hand. You can buy anything from porcelain to brass ornaments, from pipes to watches, from swords to WW II memorabilia, from hand painted scrolls to jewellery.

And kimono. Hundreds, if not thousands of them. There is a huge variety for both women and men, starting from the most basic, unlined summer yukata to the very elaborately embroidered wedding kimono. Many of the stalls have a fixed price of 1000 YEN per piece, but some special kimono can be more expensive. Other stalls sell the necessary accessories, like sandals and socks, and it should be possible to buy a full summer outfit for less than 10.000 YEN. Of course, whether the fashion conscious Japanese can tell that you are wearing a possibly out of fashion kimono, I do not know…

Anyway, I went to the flea market to buy a soroban for my class. Most of the ones I saw however, were the old, pre WW II ones, with five ichi-dama at the bottom instead of the modern four. While they are beautiful, made of heavy wood and often in very good condition, I wanted to buy one I can actually use. And, wouldn’t you believe it – I got very lucky indeed as I spotted a current model with 27 rods for only 500 YEN – about one tenth of the price of a new one! It still bears the name of the previous owner, but that’s not a problem, as it has to be cleaned anyway… I am very happy about my purchase.

Kitano Tenman-gu’s flea market is probably the biggest one in Kyoto, but there are many others at shrines and temples throughout the city and throughout each month. The dates are fixed, rain or shine, and most are from early in the morning to late afternoon at 4 or 5 pm. Here is an incomplete list of the Kyoto flea markets I know:

1st: To-ji temple

8th: Toyokuni shrine

15th: Chion-ji temple

21st: To-ji temple

22st: Kamigamo shrine

25th: Kitano Tenman-gu

Equinox

Today was a public holiday in Japan, the Autumnal Equinox Day or Shubun no Hi. Nowadays the idea is to say thank you for the harvest, a sort of thanksgiving. The holiday is a modernized version of what was called Shu Ki Koreisai, a day to pay respects to past emperors and the imperial family in general, introduced in 1878. And this day in turn probably goes back to ancestor worship in China. Note that the spring equinox is also a national holiday in Japan, with the same idea behind it.

When I was finished with my daily Japanese lesson today, I betook myself to a very small local matsuri in Omiya street, near the crossing with Imadegawa. It is in the old district of the weavers and cloth makers, and you could go into some of the old merchant’s houses and have a look. They are beautifully restored and many old pieces of furniture were on display, together with some of the traditional tools they were using. The houses had a room or two in front that once featured as a shop, then there was a small Japanese garden, and a narrow corridor next to it would lead to the private rooms at the back.

In several houses beautiful kimono were on display, and in one of them, I could watch a kimono painter at work. He was a man of at most 60 years, working in what is called the yuzen dying technique, and he explained that each of his kimonos consisted of 30 meters of silk (strips about 40-50 centimetres wide) and that one hand painted kimono needed 15 different steps of handiwork until its completion. Apparently the price for his garments is reasonable, considered that all of the work is done by hand, but I did not dare ask for a number. Unfortunately he did not answer my question as to how many hours of work one such kimono would need. It seems however, that the demand for this type of work is steadily on the decline, first because people don’t wear kimono anymore, and if they do for a special occasion here or there, the price is probably prohibitive in any case.

Abacus and Sword

The Inoyama are samurai who for generations have been in the service of the Kaga clan. Their weapon of choice, however, is not the sword but the soroban – they are expert accountants. The current head of the Inoyama family at the beginning of the Meiji restoration is Naoyuki who is called, both derogatorily and admiringly, “Mad Abacus”, for his extraordinary gift with numbers, cultivated since childhood. His pedantic nature allows him to uncover a conspiracy over disappearing rice, but, as is the fate of so many whistle blowers, he falls from grace…

The Inoyama are samurai who for generations have been in the service of the Kaga clan. Their weapon of choice, however, is not the sword but the soroban – they are expert accountants. The current head of the Inoyama family at the beginning of the Meiji restoration is Naoyuki who is called, both derogatorily and admiringly, “Mad Abacus”, for his extraordinary gift with numbers, cultivated since childhood. His pedantic nature allows him to uncover a conspiracy over disappearing rice, but, as is the fate of so many whistle blowers, he falls from grace…

From then on, the Inoyama family learns what it means to be poor, and as Naoyuki refuses to borrow money, their descent into rags is inevitable. Their struggle is not without funny moments, and in the background there is always the clicking sound of the soroban.

Abacus and Sword (Bushi no kakeibo), 2010,129 min.

Director: Morita Yoshimitsu

Cast: Sakai Masato, Nakama Yukie, Matsuzaka Keiko

This movie ties in perfectly with last Saturday’s post. 😉 Also, how Naoyuki and his family make ends meet is timeless and some of their methods to save money, although very harsh, seem applicable even today. It’s not all about economizing though. The Inoyama never lose their humour to make the best out of everything, and not for a single moment do they betray their heritage as samurai. The film is based on the book by Isoda Michifumi.

Unfortunately I could only find Japanese versions of both the book and the movie – they are available from amazon, if anyone is interested.

Yugoya

Yesterday was full moon, and this particular one on August 15th in the lunar calendar, the harvest full moon, is said to be the brightest and most beautiful of them all, and this fact drives many Japanese out to moon viewing parties. There were numerous yugoya events throughout Kyoto last night, some of them with green tea being offered, koto-recitals, or similar. However, we chose to go to Daikakuji and its pond as it is considered the best spot for yugoya. The area around the temple is still rather rural – I walked through rice fields on my way there – and the city forbids development, so the nights are dark and quiet, just perfect for moon viewing.

Yesterday was full moon, and this particular one on August 15th in the lunar calendar, the harvest full moon, is said to be the brightest and most beautiful of them all, and this fact drives many Japanese out to moon viewing parties. There were numerous yugoya events throughout Kyoto last night, some of them with green tea being offered, koto-recitals, or similar. However, we chose to go to Daikakuji and its pond as it is considered the best spot for yugoya. The area around the temple is still rather rural – I walked through rice fields on my way there – and the city forbids development, so the nights are dark and quiet, just perfect for moon viewing.

Daikakuji is one of the big Buddhist temples in Arashiyama, the westernmost part of Kyoto. It was built as detached palace for emperor Saga, and in 876 he designated it to be converted into a Shingon Buddhist temple. The origin as palace is still palpable throughout the compound: beautiful gardens lie between spacious buildings which are lavishly decorated and have amazing paintings on their sliding doors. A large part of the buildings can be visited, and yesterday at dusk, especially the old gardens made a deep impression on me. Then there is Osawa, a large lotus pond, next to the temple, which was specially laid out to resemble lake Tungting in China.

And this pond is what draws people to Daikakuji for the yugoya: Large boats cruise the pond, quietly pushed with bamboo poles, and a ride on one of those, away from the noisy people on shore, with lots of time to contemplate the moon, must indeed be quite an experience. Unfortunately, an experience we were not able to make, because by the time we arrived at the temple, all boats were sold out already.

Anyway, we took our time to see the palace/temple and at 6:30 a ceremony started with a long procession of priests taking their place on a platform prepared in the lake, the altar in the direction of the full moon, which had already risen by that time, and did look very beautiful indeed on the cloudless sky. It was an interesting mix of Shinto and Buddhist rites, with shrine maidens and Buddhist priests, something I have never encountered before. There were drums and cymbals, and the ceremony ended with a reading (or rather: chanting) from one of the Buddhist main texts.

Afterwards, we turned our attention to the food stalls on the shore: Takoyaki, udon and soba, traditional Kyoto style mochi called yatsuhashi and slightly modernized ones with strawberry filling, beer, soft drinks and shaved ice… But of course, special days call for special treats. For example, there are round white mochi with a strip of anko – red bean paste – across them, meant to resemble the moon behind a cloud. More appealing to me, however – remember that I don’t really like anko – were the little sweets in shape of white rabbits. Rabbits? Well, according to Asian tradition, there is a rabbit living in the moon…

Preparations

Lately, I have been busy preparing all sorts of stuff. For example, I went to the immigration office in Kyoto to get my visa extended. One hour later and 4000 yen poorer, I had an extra stamp in my passport, allowing me to stay yet another 90 days. The stamp, however, bears the extra note “Final Extension”, so I have marked that date on my calender so as not to forget it. Overstaying a visa is not a light issue, I have read that if the authorities have to force you out, you are not allowed to land in Japan for the following 5 years, and if you go on your own, it’s still one year. Not that I’m having plans like this, of course…

Having extended my visa means that I have some more time to find a job. I have taken one step in the right direction and registered for the next JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test – the same test that I failed last time 😉 ) which will take place in December. If you want to take the test in Japan, you can register online and pay per creditcard, all very straightforward. I just hope they didn’t expect my address to be written in Kanji…

Anyway, this means I’ll have a lot to do – studying of course, mainly Kanji and vocabulary. Grammar is limited and I’m quite confident I will manage this, but I always found learning words so incredibly boring…

Weather Warning

It’s typhoon season and we’re having bad weather again. It seems that the first 17 typhoons in South-East Asia have left us unscathed, but now that number 18 – Man-yi – has arrived, things are turning worse.

I woke up some time before six in the morning, when the rain was pattering heavily on the roofs and there was a strong wind howling, coming in through the little cracks in the window frame and rattling the doors. When I finally got to my computer about two hours later, there was a message from my landlady (sent at 6:15) asking if everything was alright. She said an extreme weather warning – something that happens only every five years or so – was issued around 5 in the morning, and some parts throughout Kyoto prefecture had even been evacuated. Neither Shinkansen nor Hankyu trains were running, and the rivers were swollen up to the bridges in some parts of the city. She said we should listen for city trucks that may come by and announce evacuations, and suggested to “follow the neighbour’s lead”. To give you an idea, here is a picture of Kyoto’s famous temple Kinkakuji (which stands in a pond) from their web cam today at 7 am:

It’s now 10 in the morning and things have calmed down. There is only a bit of drizzle, but there are strong gales here and there. The house and its inhabitants are unharmed. The forecast for tomorrow says it will be sunny and up to 29 degrees. Until the next typhoon…

Soroban

Today was my fourth soroban class. “What ” I hear you ask, “shouldn’t you study Japanese instead of something random?” Well soroban is indeed Japanese, it is the Japanese type of abacus.  The history of the soroban (lit. counting tray) goes back around 400 years, when the Chinese version of it, the suanpan (which itself is about 1800 years old) was introduced to Japan. Japanese merchants were the early adopters and had been using it since then, but it took until the 17th century for it to become popularly known, and Japanese mathematicians started to study it in depth and improve its workings. Only in the early Meiji period, i.e., at the end of the 19th century, did the soroban take its modern shape and has been unchanged ever since. Even today how to use the soroban is taught in primary schools, and you even need to pass a soroban exam to qualify for work in public corporations.

The history of the soroban (lit. counting tray) goes back around 400 years, when the Chinese version of it, the suanpan (which itself is about 1800 years old) was introduced to Japan. Japanese merchants were the early adopters and had been using it since then, but it took until the 17th century for it to become popularly known, and Japanese mathematicians started to study it in depth and improve its workings. Only in the early Meiji period, i.e., at the end of the 19th century, did the soroban take its modern shape and has been unchanged ever since. Even today how to use the soroban is taught in primary schools, and you even need to pass a soroban exam to qualify for work in public corporations.

Each soroban has a number of vertical rods or columns, each representing one digit, with five beads each. The beads are separated by a single horizontal reckoning bar into one go-dama (5-bead) on top and four ichi-dama (1-beads) at the bottom. Clearly, the more rods, the more powerful the computations that can be performed. Soroban always have an odd number of rods, the standard size has 13, in class we use soroban with 21, and my teacher gave me a small one with 11 rods to practice at home.

The basic operations of course are the same, regardless of size. The centre rod represents the one digit, the first rod to the left the 10 digit, the rod yet one further to the left the 100 digit, and so forth. To the right of the centre are the 1/10th, 1/100th, 1/1000th… rods. The four ichi-dama beads at the bottom each count as one, the go-dama bead on top counts as five, but only when they touch the reckoning bar. So, to practice a little, can you read the number below?

The beads are operated, i.e., flipped up and down, with the thumb and forefinger of the right hand. The go-dama on top is both added (moved downwards) and subtracted (moved upwards) with the forefinger, whereas the ichi-dama at the bottom are added (moved upwards) with the thumb and subtracted (moved downwards) with the forefinger. Not only this, but also the order of the movements is strictly prescribed, the reason for this is simply to increase the speed of the calculation.

There are several ways of adding and subtracting numbers, depending on how many beads are used already on the rod. Here, the concept of complements plays a very important role for computations on a soroban. For example, adding 7 can be done by

- adding 7 to a single rod (by pinching the go-dama and two ichi-dama together simultaneously), or

- adding 2, subtracting 5, and adding 10, or

- subtracting 3 and adding 10.

So far, addition and subtraction are all I can do. The concepts are easy, but it takes a while to do the finger work correctly (and fast), and sometimes, when I am all stuck in thinking about complements, I completely forget about the easy way of addition or subtraction – by simply sliding the right number of beads up or down…