In the last weeks, two of my friends have lost pets. One of my friends took in a sick kitten from the Tamayuran and gave her a joyful final week. The other lost her beloved Pekinese dog of 12 years to cancer. It’s always painful when a pet dies, they are a part of the family and often best friends on top of that.

In my family, we have always had cats and it was hard to lose them, especially when I was a child. Since we then had a very large garden next to a big forest, our dead cats were buried somewhere on our property. Not that this is officially allowed in Austria, mind you, but I guess many people in the countryside do that nevertheless.

In Japan, customs are a bit different, obviously. What happens is that there are special crematoriums where you can bring your dead pet and you will receive an urn in the end. Then you can choose to keep the urn in your home or bury it in your garden if you have one, and there are even special pet cemeteries.

Both of my friends made a point to explain that the funeral of a pet is very similar to the funeral of a human loved one. One of them showed me photos of her dead dog covered with fresh flowers before the cremation, and afterwards the urn wrapped in cloth next to a photo, some toys and dog food. This is exactly what happens in a Buddhist funeral, and once the urn is placed in the tomb, the descendants will place flowers, food, and water or alcohol on the tomb at special days like Obon.

Both of my friends made a point to explain that the funeral of a pet is very similar to the funeral of a human loved one. One of them showed me photos of her dead dog covered with fresh flowers before the cremation, and afterwards the urn wrapped in cloth next to a photo, some toys and dog food. This is exactly what happens in a Buddhist funeral, and once the urn is placed in the tomb, the descendants will place flowers, food, and water or alcohol on the tomb at special days like Obon.

What I found extremely interesting is that the urn for the dog did not seem much smaller than the urn was that contained the remains of my grandmother. In Japan, cremation for humans is not usually complete. There are bones left that are picked out by the relatives to be placed in the urn, one of the main parts of a funeral. Apparently, also for pets you receive bones and ashes, although you don’t pick them out, and you can choose which you prefer.

I’m sorry for the morbidity here, but I do find these things interesting. Probably part of my Austrian heritage?

I don’t know about you, but here in Kyoto we are having an extremely warm and dry winter so far. Temperatures are like in the middle of December, especially when it is sunny, and even when I am going home on my bicycle in the evenings, my extra thick gloves feel almost a bit too thick. And although I am getting cold easily, I am not using my space heater that often this year; yesterday I didn’t need it at all.

I don’t know about you, but here in Kyoto we are having an extremely warm and dry winter so far. Temperatures are like in the middle of December, especially when it is sunny, and even when I am going home on my bicycle in the evenings, my extra thick gloves feel almost a bit too thick. And although I am getting cold easily, I am not using my space heater that often this year; yesterday I didn’t need it at all.

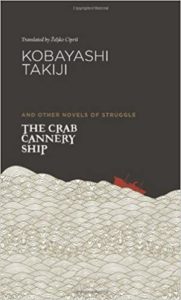

This book consists of three novellas, all written in the late 1920s/early 1930s. All three concern class struggles, the rising of the working class, and the left-wing movements in Hokkaido.

This book consists of three novellas, all written in the late 1920s/early 1930s. All three concern class struggles, the rising of the working class, and the left-wing movements in Hokkaido. Just as promised on Tuesday, here are the two most important of my New Year’s Resolutions for 2020. I do have more than these of course, but they are either very personal or too trivial/silly to share on the internet, so you’ll have to make do with these two.

Just as promised on Tuesday, here are the two most important of my New Year’s Resolutions for 2020. I do have more than these of course, but they are either very personal or too trivial/silly to share on the internet, so you’ll have to make do with these two. Finally, for New Year, I waited for my Hatsumode (the first visit to a shrine in the New Year) until January 3rd, hoping to avoid the crowds. However, I made the mistake to visit Otoyo Jinja, a usually very quiet little shrine just off the Philosopher’s Path, which happens to be Kyoto’s Rat shrine. Why is that important? Because it’s the year of the Rat, and you’d want to start it off on the right foot (and with the right deity), of course. Apparently, many, many other people had the same idea and I ended up waiting in line for 2.5 hours, just to go and do my first prayer… I don’t think I’ll be doing that ever again, but just in case, I have the proper omamori charm to prove my dedication! (Note the little tail. And the whiskers!)

Finally, for New Year, I waited for my Hatsumode (the first visit to a shrine in the New Year) until January 3rd, hoping to avoid the crowds. However, I made the mistake to visit Otoyo Jinja, a usually very quiet little shrine just off the Philosopher’s Path, which happens to be Kyoto’s Rat shrine. Why is that important? Because it’s the year of the Rat, and you’d want to start it off on the right foot (and with the right deity), of course. Apparently, many, many other people had the same idea and I ended up waiting in line for 2.5 hours, just to go and do my first prayer… I don’t think I’ll be doing that ever again, but just in case, I have the proper omamori charm to prove my dedication! (Note the little tail. And the whiskers!)