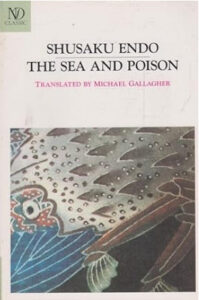

Shusaku Endo

Fukuoka University Hospital, during WWII. Dr. Jiro Suguro is a talented young intern working with tuberculosis patients. He has taken a liking to an elderly female patient and is shocked when Dr. Asai, one of the assistants, wants to perform a new procedure on her, which is likely to kill her. However, when a much younger patient dies at the hand of department head Prof. Hashimoto, the risky operation is postponed. Ostensibly to further research, but also to secure a promotion for the department head (and himself), Asai contrives a number of vivisections on a group of American prisoners. When Suguro is asked to assist at the operations, he is appalled, but at the same time unable to decline…

This book still haunts me, even though Endo avoids describing the actual murders of the Americans. Instead, we’re in the room when the operation on the young woman fails, so we have a pretty good idea what is happening later. Extremely insightful in the mind of a psychopath is the confession of Dr. Toda, another intern present at the operations. In the end, I couldn’t help feeling sorry for Suguro, who seemed to be a genuinely caring person caught up in the whole thing against his will – and haven’t we all been there before?

Sadly, this novel was not created in a vacuum. Endo based it on a true story that happened in 1945 at Fukuoka University Hospital, where the survivors of a downed American plane were killed in the name of science.

Shusaku Endo was born in 1923 Tokyo, but lived in Manchuria for the first 10 years of his life. After his parents’ divorce, he returned to Japan, where he became a Catholic in 1934. From the time he was a student, he published his writing in literary magazines, and eventually he became chief editor of one of them in 1968. He often went abroad for work, and his perspective as an outsider and Catholic has strongly influenced his novels. He is considered part of the Third Generation, the third group of influential Japanese writers who appeared after WWII. Endo received the Akutagawa Prize for “White Men” in 1954 and the Tanizaki Prize in 1966 for “Silence”. He died in 1996.

You can get this book from amazon, but I’m warning you, even 80 years after the war, it’s not an easy read.