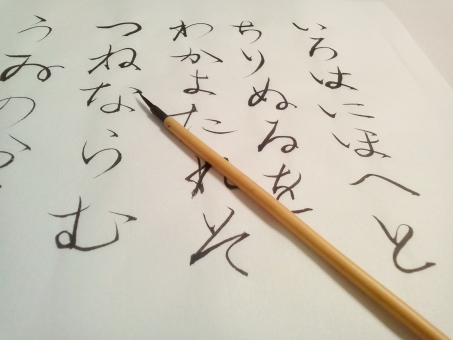

Although most Japanese nowadays write with ballpoint pens or, worse, type their thoughts into their smartphones with a single finger, traditional brush calligraphy is still held in high esteem. All kids in Japan learn calligraphy in elementary school where it is seen not only as a way to study proper hiragana/katakana and kanji themselves, on top of producing nice handwriting, but also as a means to teach patience and diligence and to build character. Many people in Japan believe that a fine piece of calligraphy always reveals the character of the writer.

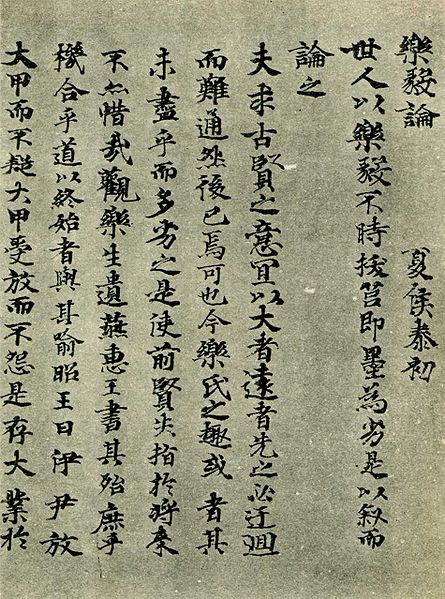

Like many other traditions in Japan, calligraphy or shodo – the way of writing – came to the country from China, where the first pictograms were invented around 2800 BCE. The Chinese script was introduced to Japan around 600 CE together with Buddhism, and the first application of calligraphy was the copying of Buddhist sutras in temples. Some 200 years later, in the Heian period, writing had been introduced to the court and its bureaucrats, and a distinctive Japanese style of calligraphy began to develop, culminating in the hiragana script.

Like many other traditions in Japan, calligraphy or shodo – the way of writing – came to the country from China, where the first pictograms were invented around 2800 BCE. The Chinese script was introduced to Japan around 600 CE together with Buddhism, and the first application of calligraphy was the copying of Buddhist sutras in temples. Some 200 years later, in the Heian period, writing had been introduced to the court and its bureaucrats, and a distinctive Japanese style of calligraphy began to develop, culminating in the hiragana script.

The hiragana script was invented as a kind of shorthand for the kanji, but over time, many of the hiragana were dropped and the script turned into a syllabary. For a long time, hiragana were considered the women’s script – in fact, women were even expressly forbidden to study kanji – but eventually, hiragana became widely accepted, and their combination with kanji created the typical Japanese writing system known today.

The hiragana script was invented as a kind of shorthand for the kanji, but over time, many of the hiragana were dropped and the script turned into a syllabary. For a long time, hiragana were considered the women’s script – in fact, women were even expressly forbidden to study kanji – but eventually, hiragana became widely accepted, and their combination with kanji created the typical Japanese writing system known today.

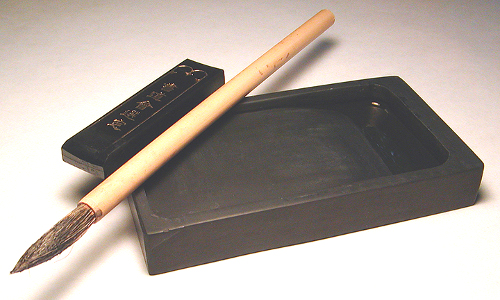

Shodo is a relatively cheap hobby to start. As a beginner, you need a brush, paper, paperweight, and ink. Many beginners start out with bottles of liquid ink, but the more serious students will not get around buying ink stick and stone to grind their own ink. Practice paper can be cheap newsprint, but more elaborate works that are meant for keeping do call for Japanese washi paper, and at that stage, a personal seal to sign – or rather: stamp – the piece will be necessary. Many calligraphers carve their own seals in special seal script characters, by the way.

Shodo is a relatively cheap hobby to start. As a beginner, you need a brush, paper, paperweight, and ink. Many beginners start out with bottles of liquid ink, but the more serious students will not get around buying ink stick and stone to grind their own ink. Practice paper can be cheap newsprint, but more elaborate works that are meant for keeping do call for Japanese washi paper, and at that stage, a personal seal to sign – or rather: stamp – the piece will be necessary. Many calligraphers carve their own seals in special seal script characters, by the way.

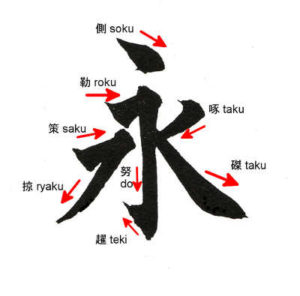

When learning to write kanji with a brush, the kanji for “eternity” is probably the best starting point, since its eight tenkaku strokes are all the different strokes that there are to master. Technically, that is. Students first start out with what is called kaisho or regular script, which has clear aesthetic rules – for example, each character should be as square-shaped as possible. Some of these rules go back to Wang Xizhi, a 4th century Chinese scholar whose calligraphy was seen as an aesthetic benchmark in both China and Japan for a long time. Kaisho most resembles the kanji printed in newspapers and books.

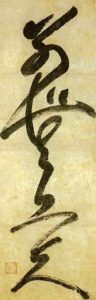

The next step for the learner is gyosho or semi-cursive script, which resembles handwriting and works with a number of simplifications and abbreviations, so to speak. The last step is sosho or cursive, where the easy flow of the brush is paramount. It is very individual, and closer to art than to legible writing. Many people cannot read texts written in sosho they are not familiar with.

The next step for the learner is gyosho or semi-cursive script, which resembles handwriting and works with a number of simplifications and abbreviations, so to speak. The last step is sosho or cursive, where the easy flow of the brush is paramount. It is very individual, and closer to art than to legible writing. Many people cannot read texts written in sosho they are not familiar with.

Not only the way each stroke is written is important, also the order in which this is done. Some people insist that only kanji that were written in the correct stroke order possess aesthetic merit and are pleasing to the eye.

Since shodo is a rather cheap hobby, many people in Japan practise it. It is a form of applied art deeply connected with Japanese spirit and culture. As already elementary school children learn the basics, they can take part in the popular kakizome ceremony, where people of all ages write down their wishes for the New Year. This often takes place in temples or shrines, for example in Kyoto, Kitano Tenmangu is very popular for kakizome. The best pieces of calligraphy are exhibited afterwards and may even win a prize. Also connected to the New Year are the nengajo postcards. Although nowadays, many of them are simply printed out, especially older people still write and address them by hand, thus showing off their penmanship.

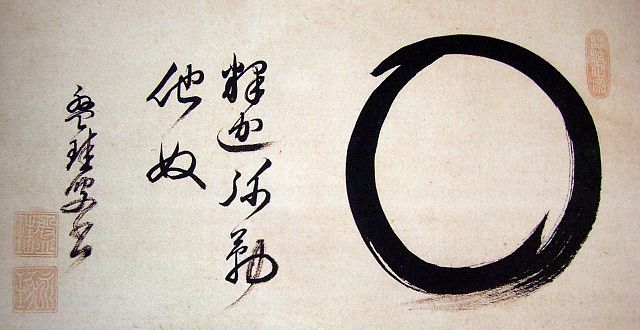

Zen calligraphy is a special form of calligraphy practised by Buddhist monks in particular. Since black ink on white paper is rather unforgiving and shows every mistake and even hesitation, the idea is that there is but one chance to get it right on a particular piece of paper. In order to produce good Zen calligraphy, the writer must completely clear his mind and let his body and subconscious do the work. This spiritual state of mind is called mushi, and hitsuzendo means “zen way of the brush”.

Zen calligraphy is a special form of calligraphy practised by Buddhist monks in particular. Since black ink on white paper is rather unforgiving and shows every mistake and even hesitation, the idea is that there is but one chance to get it right on a particular piece of paper. In order to produce good Zen calligraphy, the writer must completely clear his mind and let his body and subconscious do the work. This spiritual state of mind is called mushi, and hitsuzendo means “zen way of the brush”.

Finally, calligraphy also stands at the beginning of each tea ceremony: The guests are invited to look at a piece of calligraphy before the ceremony begins (also as a way to clear their minds) and often, there is also a calligraphy placed in the tokonoma alcove of the tea room.

Modern Japanese calligraphy was developed in the 1930s, when many new schools of calligraphy emerged that advocated creating a new, distinct style of Japanese calligraphy, rather than adhering to old, pre-Edo aesthetics. There are stunning modern pieces that are more reminiscent of paintings than of writing, and are definitely worth checking out.

If you want to know more, especially about calligraphy history, see this page on Japanese calligraphy.